Article / Ukraine's accession path to the EU - A Decade of Disillusionment

Introduction

From Revolutionary Hope ...

The Orange Revolution of 2004 gave life to great hopes in Ukraine and abroad. Once the old regime - represented by Kuchma and Yanukovych - was defeated, Ukraine seemed on a rapid path to democracy and European integration. Ukraine’s pro-EU commitment had strengthened over the years, and the EU’s normative power and economic incentives reinforced their influence on Ukraine's trajectory. The gradual integration of European norms and values into Ukrainian political discourse solidified the country's pro-EU orientation. Similarly, protests in Russia in early 2005, which were directly inspired by the Orange and the other colour revolutions - but sparked by a government change in social welfare benefits, not electoral fraud - underscored how the democratic momentum reverberated in the whole region, fuelling hopes for political liberalisation across the post-Soviet space.

After their respective colour revolutions, Moldova, Georgia, and Ukraine sped up regional collaboration in an attempt to anchor democratic reforms and reduce Russian influence. Through subregional alignments like the GUAM (Organisation for Democracy and Economic Development) together with Azerbaijan and the Community of Democratic Choice, they started promoting democracy in the post-Soviet space as "locomotives" of change. They also pushed for greater EU involvement in the efforts to bringing a change in the frozen conflicts that erupted in the early 1990s in Transnistria, Abkhazia, and South Ossetia, highlighting the emergence of a new Eastern bloc resisting Moscow's hegemonic ambitions.

The EU had benefited in coherence of its foreign policy from the 2004 events - the Orange Revolution itself, but also the EU enlargement to Central and Eastern European countries (CEECs). Although tensions among older member states continued to exist - e.g., Germany's and France's pragmatic strategy of approaching Moscow based on energy interests and historical concerns - the joining of member states like the Baltic ones and Poland brought in new priorities. These new members, guided by their own experiences of the Soviet era, considered Russia as a threat to security and promoted a more robust pro-democracy stance. In supporting Yushchenko's democracy drive in the Orange Revolution, the EU was led by Polish and Lithuanian diplomatic activism. For the first time, the EU openly supported a democratic uprising in the post-Soviet region, laying the basis for a more value-oriented policy in relation to its Eastern neighbourhood.

... To Political Paralysis

As we have anticipated in the previous section of this article, this momentum quickly wore off. The new Orange political cycle did not get off to the best start. In fact, key symbolic events such as the investigation of journalist Gongadze's murder and the poisoning of Yushchenko remained unsolved, fuelling scepticism about the elite's commitment to justice. Furthermore, while the Orange Revolution had promised systemic renewal, the post-2004 leadership soon abandoned revolutionary cohesion for factional conflict, leaving aside the people's hopes for meaningful democratic change. The reform coalition dissolved quickly under internal struggles between President Yushchenko and Prime Minister Tymoshenko, both central leaders of the Orange movement. Public frustration mounted as they failed to transform revolutionary aspirations into real policies.

In September 2005, Yushchenko dismissed Tymoshenko’s entire government amid mutual accusations of corruption and economic mismanagement. At the end of 2005, only about one in seven Ukrainians still fully backed Yushchenko, from nearly half a year earlier. Yushchenko's moves marked the beginning of a decline in his popular support, as the economy stagnated and the Orange coalition broke up into competing camps. The political cost of factional conflict became increasingly high: with the parliamentary elections in 2006, Yushchenko's Our Ukraine resulted well behind Yanukovych's Party of Regions (32%) and Tymoshenko's blocs (22%), with just 14% of votes. While this outcome will be scrutinised in detail below, it shows how Yushchenko's inability to sustain coalition unity not only weakened the reform momentum but reshaped the political landscape to the advantage of both his former rival and his former ally.

Despite political instability, the post-Orange period was marked by relevant institutional reforms, realised through constitutional amendments passed in 2004 and entered into force in 2006. Yushchenko had, in fact, made a significant concession by agreeing to back a constitutional amendment that would increase the powers of the parliament and the prime minister while limiting the ones of the presidency. Moreover, a fully proportional electoral system was introduced in order to encourage pluralism and party consolidation. These reforms allowed Ukraine to move away from the hyper-presidentialism of the old regime and to build a more balanced system of governance and a more diffused division of powers.

Unfortunately, though, as we will explain later, the reforms were partially overshadowed by political fragmentation, weak coalition discipline, and pervasive patronage networks. Nevertheless, they set a crucial precedent in making the political environment more competitive and accountable - establishing the institutional groundwork for the EU's increasingly conditionality-oriented approach to encouraging integration, more linked to domestic reforms by the ENP and the Eastern Partnership.

An Half-Open Door: Integration Without Accession

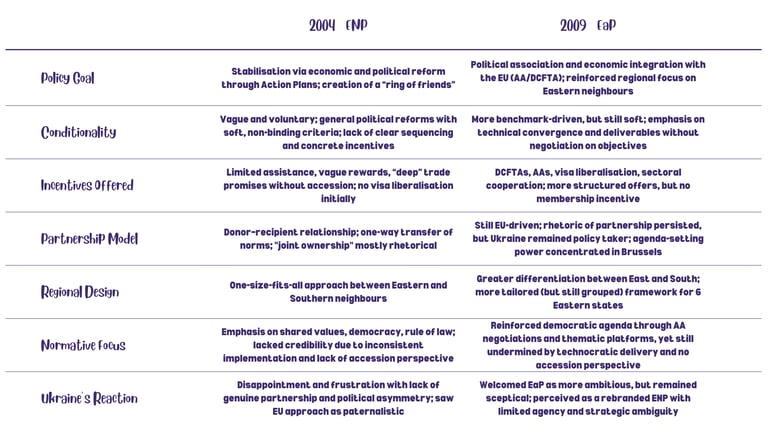

The European Neighbourhood Policy: A Democracy Twist with No Membership Prospect

As we have already mentioned in the previous section, in 2004 the EU launched the European Neighbourhood Policy (ENP), designed to enhance the EU’s relations with its neighbours and assist the EU enlargement to the east. Without necessarily providing a concrete perspective of membership, the ENP offered a framework for collaboration, better binding the EU to its neighbours and aiming at advancing market economy and democracy in the region. In the immediate post-Soviet era, technical assistance measures for the political and economic transition processes were the main emphasis of the EU, with security components added towards the end of the 1990s. With the ENP, the EU planned to stabilise the region as a “ring of friends” - as formulated in 2002 by European Commission President Romano Prodi - shaped in its own interests.

This new policy represented a key shift in the EU’s neighbourhood policy with what has been referred to as a "democracy twist" vis-à-vis Russia. In fact, during the 1990s, Brussels had had a "Russia first" approach driven by both geopolitical considerations and the hope that Russia might become a democratic partner. Thus, the 1994 Partnership and Cooperation Agreement (PCA) with Ukraine, for example, was mostly a diluted version of the one with Russia. In the early 2000s, Russia had shown interest in establishing a strategic alliance with the EU, not only for trade and energy cooperation, but also to work on a common security architecture in Europe. The two actors seemed to collaborate in what would become a shared neighbourhood, notwithstanding the upcoming EU’s enlargement.

Still, and erroneously, the EU viewed Russia as progressing towards democratic norms and European values, while Russia viewed the EU as geopolitically weak and unwilling to extend its influence into the post-Soviet space. These misplaced hopes emerged with the launch of the ENP, perceived by Moscow as the first real incursion of its 'near abroad' - an expression coined by the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in the early 1990s and reflecting the ambiguous connections that Russia established with post-Soviet countries. The Orange Revolution in Ukraine drastically changed the two actors’ perceptions, triggering alarm bells in Russia regarding its declining role in the region. As their neighbouring countries were increasingly becoming an object of contention, the possibility of cooperating over a shared neighbourhood was overshadowed by the realpolitik of playing in a contested neighbourhood.

Russia's authoritarian trajectory moved increasingly away from Ukraine's democratic mobilisation of the Orange Revolution. In this context, Ukraine's ENP Action Plan, approved in 2005, was among the most ambitious in the region to focus on democratic standards, rule of law, and good governance. Despite divisions within EU institutions and member states, the new strategy placed political conditionality and European standards at the top of Brussels' approach to Kyiv. On the other hand, and in the same year, Russia refused to participate in the ENP and agreed on four Common Spaces with the EU (Economy; Freedom, Security, Justice; External Security; Research, Education, and Culture) that lacked specific commitments on democracy.

This imbalance allowed the EU to bring in Ukraine and Russia under the same framework but with extremely different goals and instruments. The ENP offered neither the membership incentive nor the conditionality that could be imposed. Whereas ENP Action Plans outlined general political reforms, their implementation was made subject to the voluntary actions of Ukraine and the credibility of the EU was weakened by imprecise rewards and unbalanced commitment of member states. On the other hand, Russia did not accept being treated as a “neighbour” or conditionality target, and managed to win a framework clearly avoiding political reform standards.

This divergence had significant spillover consequences for the efficacy of the ENP in Ukraine. Moscow's strategic use of the Four Common Spaces permitted it to position itself as a counter-normative pole not merely by rejecting EU-style conditionality, but by actively weakening it. Russia's diplomacy worked to depopularise EU integration among Ukrainian elites by offering selective incentives like cheap gas to compensate the costs associated with conformity to EU standards. At the same time, the EU logic of long-term integration envisaged that its neighbours would undertake great and politically costly reforms without an aligned membership prospect. Thus, the Four Common Spaces not only weakened Brussels' normative capacity over Kyiv but helped maintain an ambiguous environment in which Ukraine could oscillate between the two poles. The pressure from Moscow to delay or dilute application of the ENP Action Plan, especially during the presidency of Yanukovych, hints at the fact that competition between the two architectures had concrete and immediate implications on Ukraine's reform trajectory.

Interestingly, the ENP’s inefficiencies allowed for superficial balance between the EU and Russia. Russia was officially excluded from the policy but its loose integration model and vagueness entailed that Russia did not perceive the ENP as a serious challenge. The cooperation between the EU and Russia was still largely declaratory, and each actor had parallel policies in Eastern Europe. At the same time, the 2004 EU enlargement considerably extended their shared border, with Kaliningrad becoming a Russian enclave within the EU.

Looking Back at the ENP: A Limited Vision for Inclusion

A Policy Without Vision: The Structural Limits of the ENP

Ukraine's response to the ENP defied the structural limitations of the policy. Indignant at first to be grouped with North Africa and the Middle East, Kyiv chose to comply with the ENP as a temporary measure to be reoriented towards deeper integration. But the 2004 negotiation of Ukraine's Action Plan was rough. The Kuchma administration considered the EU offer too limited, and even after the Orange Revolution, Brussels resisted Ukraine’s insistence on a more ambitious and symmetrical framework. Instead, the EU in February 2005 unilaterally issued a 10-point letter of "additional measures" aimed at making the offer sweeter. But those measures entailed a roster of conditions placed solely on Ukraine with very few on the EU side. In addition, while these measures tightened various ENP provisions, like pre-negotiation on visas and market economy status recognition for Ukraine, the framework remained marked by low political aspiration. Conditionality, where it existed, was vague, half-heartedly monitored, and progressively diluted.

Apart from its conceptual flaws, the ENP also suffered from institutional inconsistency. Officials in Brussels used to consider the neighbourhood policy in purely technocratic terms, leaving its implementation fragmented and placing full responsibility on the partners themselves. This depoliticised and executive-driven model clashed with the policy's ambitions of "joint ownership". Member states admitted that in the absence of a membership perspective, reform would remain half-hearted. Concretely, the EU offered neighbours a "take-it-or-leave-it" choice, one that most found limiting - especially those, like Ukraine, who aspired to greater inclusion but were denied full status in setting the agenda.

Ukraine's Disappointment and the Search for Agency

While Kyiv officially endorsed the 2005 Action Plan, both government and parliament officials revealed deeper disappointment, speaking about the ENP as incoherent, under-resourced, ill-managed and missing strategic direction. They lamented the absence of genuine partnership: "we come with a lot of ideas, but the EU has its own priorities”; “we are not equal by definition, or at least this is what we are led to believe". In criticising the ENP's deficiencies, Ukrainian policymakers pointed out that despite making recommendations, they were faced with top-down EU priorities. As the EU conditionality often resulted counterproductive, the lure of a deep free trade area served to do little to inspire reforms, and without an accession track with credibility, Ukrainians began to see the EU way as more and more paternalistic.

Ukraine was placed under a low-incentive partnership framework that was unable to change its post-revolution dreams and geopolitical interests. The EU lost the post-revolution window of opportunity to realign its strategy to Ukraine's specific situation and reformist momentum. Rather than embracing the new political forces and civil society emerging from the Orange camp, Brussels welcomed continuity and incrementalism.

The ENP was found to be in conflict with the post-Orange leaders’ dreams. The 2005 Action Plan was set to use EU aid for Ukraine's democratic transformation. But it fell short of what the Orange movement had called for, which was a firm emphasis on justice, accountability, and political renewal. While Kyiv requested a roadmap toward accession to the WTO, market economy status, deep reforms aimed at combating corruption, and progress towards EU membership, the ENP offered instead a menu of technocratic priorities with no sequencing and no binding incentives. No blueprint was offered for institutional reforms that would have addressed the crisis of legitimacy of the new-Orange era. The absence of an accession horizon, especially after the 2004 EU enlargement, only served to fuel Ukrainian discontent.

The Ukrainian government attempted to close the gaps by presenting a complementary "Roadmap" in April 2005, enumerating over 300 legislative and administrative steps designed to give the Action Plan substance. Where the ENP text had been vague - areas of foreign and security policy or visa liberalisation - the Roadmap offered precise deadlines. Implementation was not easy, though, as Yushchenko's administration didn't enjoy stable parliamentary backing - much of the legislative measures were stalled, awaiting the 2006 elections. While certain chapters, such as regional diplomacy or Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP) coordination, had progressed, fundamental reforms in judicial independence, anti-corruption, or public broadcasting remained on paper. In addition, Ukraine's expectations on visa facilitation were countered by Brussels' cautionary approach. The 2006 visa facilitation agreement - a top Ukrainian priority excluded from the ENP at first - was finally achieved, but with minor results than expected. The Action Plan remained more of an overall direction tool than a transformative one, lacking the sort of benchmarks, strategic vision, and reward structure that had marked previous enlargement waves.

In contrast to the enlargement process, where regular progress reports had been a central instrument of both pressure and reward, ENP monitoring was also milder and less detailed. Interestingly, Brussels did not use negative conditionality: there were no tranches of assistance suspended, and no consideration of suspending negotiations with Ukraine even during the 2007 political crisis (see under). Although the EU could have suspended technical assistance, it did not, and the negotiations on the new agreement continued without interruption.

The absence of a membership perspective only fed mistrust: had there been such a perspective, Ukraine would have been more willing to absorb EU conditionality, but without it, the EU approach was seen as paternalistic and not considering Ukraine's own agency and geopolitical interests. Not to mention that in 2004 10 states entered the EU, after being locked into a fast track for membership. Moreover, eight of them were former communist countries of Central and Eastern Europe, with two more to follow in 2007. Many of them were also quite supportive of a greater EU engagement with Ukraine, including the necessity to acknowledge it as a potential member state. Ultimately, the absence of a membership horizon not only eroded the legitimacy of EU conditionality but also disempowered pro-European reformist forces in Kyiv, which had limited bargaining leverage in shaping the direction of bilateral cooperation.

As a result, though the rhetoric of the ENP was of building a "ring of friends" and promoting stability and prosperity in the EU's neighbouring regions - both in the East and in the South - the policy was weakened by internal contradictions. It tried to reconcile an idealistic inclusion logic with a security-minded realist agenda, but this created tension that weakened its strategic consistency. The policy offered economic integration in the future but without a route to membership, so its inducements were too feeble to trigger radical reforms. Eastern neighbours, like Ukraine, responded anxiously, perceiving the policy as having to offer "special" or "privileged" relations without concrete substance. The early ENP’s limited incentives, ill-defined benchmarks, fuzzy rewards and vague conditionality made it difficult to respect the ENP Action Plans.

Though claiming an emphasis on "shared values," "joint ownership," and "mutual interests," the ENP worked more on an external model of governance than true partnership. On the ground, the EU established a donor–recipient, one-way relationship, transferring its institution-building model without compromising on the neighbours' own strategic agenda. The EU expected adaptation to its norms and largely kept partner states' agency out of the equation, treating them as "objects of governance" rather than fully fledged sovereign players. The inconsistency undermined the EU's declared desire to foster cooperation and established a culture of inequality, particularly in countries such as Ukraine, which felt their political interests were side-lined by a Eurocentric agenda.

The structural limitations of the ENP undermined its role as a transformative instrument. Unlike the process of enlargement, which offered both legitimacy and substantial material incentives for reform, the ENP lacked the key leverage of accession. The EU attempted to exert its normative power through asymmetrical bilateral relations and conditionality, yet without the accession legitimising promise, such requirements lacked credibility and mobilising potential. The ENP's carrots of economic aid and promises of deeper integration were not sufficient to offset the political and economic cost of domestic reforms. The contrast with the robust enlargement toolkit of - economic assistance, institutional incentives, and political cover - was revealing. In this context, the ENP seemed a failed attempt to retain the normative influence made possible by the enlargement instrument.

The failure of the ENP to take lessons from regional diversity and complexity further eroded its legitimacy. Its design ignored key differences among partner states on geopolitical, cultural and civilisational matters. On one hand, Ukraine had found itself caught in the middle between the EU and Russia with no assurances from either side. On the other, when Ukrainians claimed their European identity, they also acknowledged rooted Soviet legacies and the lack of European political culture. The perception of Europe patronising its eastern neighbours and the failure to deliver differentiated outreach and tailored incentives made the ENP look out of touch with realities on the ground.

Importantly, the EU support of democracy in Ukraine underwent considerable transformation with the introduction of the ENP. Before it, EU democracy support relied on the TACIS (Technical Assistance to the Commonwealth of Independent States) programme and the EIDHR (European Initiative for Democracy and Human Rights). Yet, both mechanisms proved to have limited impact. TACIS was predominantly concerned with economic reform and control of the borders with very limited resources devoted to civil society, justice reform, or independent media. In addition, TACIS aid was directed through government institutions with little scope for interaction with non-government actors. EIDHR aid to Ukraine was also minimal, and the difficult application process made access to most NGOs difficult. With the launch of the ENP and its European Neighbourhood and Partnership Instrument (ENPI) – in lieu of the TACIS - democracy promotion entered a new stage. Democratic development and good governance received priority in the new financial framework and were allocated a significant share of resources. At the same time, the renewed EIDHR (as European Instrument of Democracy and Human Rights) facilitated access for and involvement of civil society organisations.

Shifting Coalitions and the Collapse of the Orange Bloc

The failure of the Orange coalition to translate revolutionary solidarity into sustained political organisation or integrated policy agendas paved the way for its collapse. In the absence of strong party institutionalisation and a shared strategic vision, the Orange camp soon degenerated into factional battles and opportunistic alliances, ultimately eroding public trust and opening the door for the re-assertion of the ‘ancien régime’.

From 2005 onward, Ukraine entered a cycle of unstable governments and shifting coalitions. As we already mentioned, Tymoshenko’s first premiership collapsed in September 2005. One of the key reasons for the Orange regime's loss of popularity was its failure to institutionalise a structured, ideologically grounded political party. Rather than mobilising a political party behind the already established "Our Ukraine" parliamentary group, Yushchenko opted to build a new formation around the loose civic movement "For Ukraine! For Yushchenko!", mainly made of government loyalists. This decision watered down the political identity, too vaguely based on values such as democracy, anti-authoritarianism, and Europeanness, eventually weakening the unity of the Orange bloc.

After the 2006 parliamentary elections, the Orange camp’s narrow majority was put under pressure by internal tensions. Yushchenko refused to surrender power to Tymoshenko's now-stronger block and refused to ally with her. During negotiations, the Socialist Party defected to join Yanukovych's Party of Regions (PoR) and the Communists allegedly in exchange for bribes. In an attempt to prevent Yanukovych from governing alone, Yushchenko formed an unlikely alliance with centre-right party Our Ukraine and the PoR, allowing Yanukovych himself to return as prime minister - two years after he was removed by the Orange Revolution.

The return of Yanukovych as prime minister triggered a new crisis. Once in office, he and his allies tried to consolidate power, driving Our Ukraine ministers out and manipulating institutional rules in order to coerce oligarchs back into the Party of Regions. Yanukovych also targeted the rules of the constitution itself, seeking a two-thirds majority in parliament by buying deputies despite the "imperative mandate" rule introduced in 2006 specifically to prohibit such practices. This led to a constitutional crisis in 2007, as Yushchenko sought to dissolve the Ukrainian parliament, the Verkhovna Rada, and tensions escalated to the point where troops were deployed around government buildings. At last, snap elections were announced for September 2007.

Surprisingly, the elections created a third chance for the Orange parties. Tymoshenko's bloc emerged as the strongest force. Yushchenko was forced to reappoint her as prime minister in December 2007. This time her government lasted over two years, but it coincided with the world financial crisis, which hit Ukraine hard as GDP shrank by 15% in 2009. Tymoshenko's failure to articulate a clear reform agenda, coupled with bailout packages favouring oligarchs, eroded her credibility, and generated among the public the impression of mismanagement of the economy. Meanwhile, Yushchenko continued to undermine her efforts, deepening the dysfunction of the Orange leadership.

By the 2010 presidential elections, even Yushchenko, who once embodied democratic renewal, was seen as weak and compromising, after having formed coalitions with his former rival. The political rivalry between him and Tymoshenko, coupled with the poor governance put in place by the orange camp, had eroded public support for the reformists. These dynamics ultimately allowed Viktor Yanukovych to return to the stage, this time as a legitimately elected president - but after years of political manoeuvring that led him to gain considerable authority and strengthen the PoR. The Orange Revolution, which had promised a new democratic era for the country, ended with the return to power of the one person it had tried to exclude. The breakdown of Ukraine's post-Orange constitutional fixes, combined with the failure to bring about real reforms, exposed the weakness of its democratic change, fueled ever-growing public disappointment, and paved the way for an even more radical rupture in 2013.

The Eastern Partnership: More Ambition, Same Asymmetry

In 2009 the Lisbon Treaty entered into force, establishing the European External Action Service (EEAS) and the High Representative (HR) in order to improve the coherence of EU foreign policy - even though scholars believe it didn’t have much impact in that sense. More importantly, in the same year, the EU launched the Eastern Partnership (EaP) - interestingly, one year after Russia’s war in Georgia. But the main objective was to strengthen political association and economic integration between the EU and its Eastern neighbours.

This was to be achieved by replacing the existing Partnership and Cooperation Agreements with Association Agreements (AA), the establishment of Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Areas (DCFTA), the liberalisation of visas between the EU and its partner states and, finally, increased sectoral cooperation, for instance in the energy area. The EaP was marked by a greater degree of differentiation of the EU's approach towards its Southern and Eastern neighbours, who were previously treated more equally within the framework of the European Neighbourhood Policy.

The EaP thus represented a refreshed framework offering greater differentiation, more structured cooperation, and engagement with civil society. The new policy combined thematic platforms of cooperation (e.g. good governance, energy, convergence with the acquis) and flagship initiatives intended to generate greater ownership and visibility. This way, the EaP sought to address the ENP’s credibility deficit by offering more tailored and ambitious partnerships. From Ukraine's perspective, the EaP represented a right step in the direction of EU membership, despite its inconsistencies. Ukraine's advancement towards integration had been in fact consolidated with the launch of talks for a new Association Agreement with the EU, in 2008.

In the middle of deteriorating relations between Russia and the West, fuelled by the threat of NATO expansion, and the 2008 Russian war in Georgia, the EaP further increased Russia's suspicions about the EU. The shift from soft cooperation towards more legally binding integration, through AA and DCFTAs, was quite troubling for the Kremlin, as these tools implied not just alignment with the EU legal framework but also economic and political integration in the long run. Unlike the ENP, the EaP, with its clearer regional design, was perceived as a direct threat to Russia’s sphere of influence. As the EU and Russia developed increasingly different integration formats, their neighbourhood became a field of open competition.

The EaP was viewed in Moscow less as a diplomatic effort and more as a geopolitical provocation. Its design, aimed at binding Eastern partners into the EU regulatory sphere, was interpreted by Russia as an effort to prevent the Kremlin's own influence over its neighbourhood. In turn, the Kremlin narratives increasingly positioned the EaP as a coalition of states opted into EU influence, in part because, even without Russia's inclusion, any policy not involving the Kremlin would be regarded by Moscow as aimed against it. Tensions grew as EaP negotiations progressed: in May 2010, Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov warned that the "EU's Eastern Partnership program can harm Russia's relations with the CIS countries", adding that any Russian participation would require that their interests should be taken into account at early stages when discussing the single projects.

Despite its new language, the EaP still inherited the conceptual and architectural flaws of the ENP. According to some scholars, it reproduced the ENP’s hard push for regionalisation - creating regions that would not exist outside the framework of the cooperation with the EU - this time focusing on the Eastern neighbours. In fact, scholars questioned the way of grouping together under a single policy Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Georgia, Moldova, and Ukraine, without the other post-Soviet states.

Moreover, the EU continued to present the relationship as one of external governance, exporting its own political and institutional model without in fact empowering its partners. The partnership remained residual and symbolic, and the policy was often little more than a means of EU norm and interest imposition. EU policymakers still lacked a vision of how to implement it and kept placing the burden of reform on the partner states. The EaP was thus seen as a prolongation of the EU approach where neighbours were offered cooperation on EU terms, with no negotiation on priorities or jointly resetting objectives.

Ukraine's response to the EaP reflected frustration with the rhetoric of equality that masked real asymmetry. Ukrainian officials described the policy as uncoordinated and lacking adequate resources and strategic direction. They saw no real partnership, mutual trust, or influence on EU priorities. While the EaP promised "joint ownership", the EU remained the sole agenda-setter, and Ukraine the mere recipient. Again, the absence of a membership perspective was a major cause of dissatisfaction: representatives openly stated that without this kind of offer, they did not have much to gain from fully accepting EU conditionality. The perception that the interests of Ukraine took second place to EU interests considerably impaired the reputation of the EaP as a "new" initiative.

Although the EaP aimed to create greater differentiation, it did not address the identity and geopolitical issues of the region. Countries like Ukraine continued to find themselves in between the EU and Russia as well as facing domestic divisions and socio-cultural legacy. Several Ukrainians noted that the EU approach remained too technical, and too little focused on local conditions and regional heterogeneity. The emphasis on normative convergence rather than membership, and the residual sense of alienation and Eurocentrism, reinforced the impression that the EaP was merely a rebranded ENP, not a qualitative advance. It therefore struggled to be seen as a credible and effective policy tool capable of piercing the political complexity and strategic competition within the region.

Domestic malfunctioning of Ukraine was deeply rooted in Ukraine's failure to deliver on the reform agenda. Democracy quality in Ukraine decreased between 2010 and 2014, undermining the ability of Ukraine to converge towards the rule of law and governance standards of the EU. Reform of public administration remained a symbolic process, and anti-corruption could not go beyond declarative policy. Withholding the highest EaP funding at the time did not allow Ukraine to convert it into tangible reforms. It was notably lagging behind on judicial reform, human rights protection, freedom of information, and the proper use of EU funds.

Conversely, the EU praised Moldova as a "success story" of EaP between 2012 and 2014. Although subsequent backsliding revealed structural vulnerabilities, Moldova initially made strides toward EU approximation. Georgia also showed more stable progress, with a pluralistic politics and active media. While the two countries also experienced serious issues of judicial independence and high-level corruption, their initial reform trajectories seemed more rational and credible than those of Ukraine. The gap was in part one of domestic political will, but also one of state capacity to embrace EU conditionality and deliver on benchmarks.

The EaP proved too technocratic, with the EU demanding a lot but committing too little. These problems were to some extent a reflection of deeper EU member state divides over ambition and scope of the Eastern Partnership, whose design was in fact shaped by cross-cutting national agendas. Countries such Czechia, Poland, Slovakia, the UK, the Baltic and the Scandinavian member states were the most proactive, advocating closer integration with Ukraine as well as requesting ambitious AAs and DCFTAs. Their stance focused on political and economic convergence, particularly in response to democratic aspirations generated after the Orange Revolution. On the other hand, less supportive member states - especially France, Benelux countries, and some Southern European countries - were not ready to endorse a membership perspective. Although France also softened under President Sarkozy, even proposing an AA in 2008, it opposed isolating Ukraine from other ENP countries. Germany, although retaining its traditional interest in East Europe, remained cautious.

These rival visions had created a compromise architecture: bold in the scope of some of its longer-term ambitions, but eventually technocratic in form, relying intensely on benchmarks and soft conditionality. More generally, Eastern Europe failed to follow the EU-based model according to which political cooperation follows economic integration. The dysfunctions of local societies, whose main political issues were the absence of democracy and human rights and the persistence of oligarchies, required greater attention from the EU.

Table 1: ENP (2004) vs EaP (2009)

A Contested Neighbourhood: Two Diverging Frameworks of Integration

In 2010, Russia launched the Customs Union, representing an important milestone of its policies in its neighbourhood. Before that, Russia had mainly used short-term policies and incentives. But what would become the Eurasian Economic Union (EEU) in 2015 was intended as a long-term endeavour, with the dual aim of strengthening relations with post-Soviet countries through comprehensive integration and obstructing the EU’s EaP. Full membership in the Russian-led organisation and a DCFTA were mutually exclusive, therefore countries like Ukraine therefore regarded the EU and Russia as alternative markets, based on different standards and practices.

Russia’s approach to integration was of course very different from the European one. If the European project has been based on voluntary commitments, the Kremlin relied on coercion to discourage Eastern partners from integrating with the EU. Faced with the rising attraction of the EU, Russia had begun to cause instability in Ukraine, Moldova, and the South Caucasus. This step represented a relevant shift from passive influence to active obstruction, revealing the Kremlin's priority to reassert long-term control over the region and prevent its drift toward the West.

Even with its assertive tone, Russia's model was not attractive enough. While it offered immediate incentives, such as cheap energy or market access, its development trajectory was not widely seen as desirable. By contrast, the EU, with the ENP and EaP, offered a frame for institutional reform, political and economic modernisation, and possible long-term prosperity, even without the promise of membership. The difference of these models is also to be found in the different identities of the two actors. The EU has been often portrayed as a normative power - values and ideas based on universal principles - with the aim of eventually bringing stability and prosperity, as it was the case in post-war Western Europe and post-Cold War Central and Eastern Europe. Russia has instead been regarded as a realpolitik-oriented actor ready to employ a wide range of policy instruments, including coercion, to oppose Western objectives.

"Russia makes you an offer you can't refuse; the EU makes you an offer you can't understand" goes a popular joke in Eastern Europe. Beneath the jokes lies a more profound reality. Moscow's promises were normally hasty and vigorous, but not transformative; Brussels' promises were less transparent, slower to materialise, and sometimes hard to read, but promised systemic change. The former could offer short-term stability or gain; the latter required costly reforms with distant payoffs. This tension between proximity and opacity characterized the manner in which elites and societies throughout the region viewed their options for foreign policy.

The EU’s internal divisions concerning Russia made it difficult to put forward a coordinated response to Russia's geopolitical assertiveness, especially because of its Russian gas dependency. Some member states, like Slovakia and the Baltic States, were particularly dependent on Russian imports, due to the Soviet-era infrastructure, while others, like Spain, were not dependent at all. But even among the former there were strategic divergences: the Baltic States wanted to reduce their dependence for national security reasons, while Italy was actively seeking closer energy cooperation. Member states’ visions also diverged on how to manage Russia's continued use of gas as a political weapon, as some feared to provoke the Kremlin for the sake of their energy needs. The 2006 and 2009 cut-offs in Europe prompted some emergency responses - energy diversification, interconnect infrastructure - but the initial momentum faded by 2010 and deep structural dependency remained. Germany, for example, opted for energy diversification via the Nord Stream pipeline (initiated in 2011), reducing its dependence on transit through Ukraine but increasing the one upon Russia.

From Hesitation to Revolution: The Road to Euromaidan

Yanukovych's Authoritarian Turn and thee Stalled AA

After his election, Viktor Yanukovych moved to dismantle the post-Orange Revolution checks and balances. By using illegal party-switching in parliament due to bribery and intimidation, he brought down Tymoshenko's parliamentary majority and secured control of the Rada. This political move provided a base for a regressive constitutional rollback that restored sweeping presidential powers with what many analysts referred to as a constitutional coup. Critical judicial reforms also undermined the rule of law, placing judicial institutions under the authority of the executive power.

Yanukovych's consolidation of power was followed by an unprecedented wave of political persecution of the opposition, including Orange leader Yulia Tymoshenko who was imprisoned in 2011 on dubious charges. Meanwhile, corruption became deeply rooted and centralised. Power and wealth concentrated within Yanukovych’s tight inner circle - "the Family" - which monopolised state resources and dictated law enforcement. Yanukovych’s regime signaled a shift from oligarchic pluralism - under Kuchma - to personalist authoritarianism, where state institutions were subordinated to private enrichment and authoritarian dominance.

Since Viktor Yanukovych became president, he worked more closely with the Russian leadership than any previous Ukrainian administration. While showing pro-EU rhetoric and cooperation, he rejected integration with NATO and kept close ties with the Kremlin, appointing pro-Russian politicians and, in return for cheaper gas, consented to prolong Russia's military presence in Crimea until 2042. His renewed authoritarian direction for the country was not well regarded by the EU. The 2011 Tymoschenko’s imprisonment caused a diplomatic freeze in EU–Ukraine relations, putting the AA on hold even after its technical completion. Brussels saw Tymoshenko’s case as emblematic of Ukraine’s backsliding on democracy and the rule of law.

As Yanukovych's electoral reforms enabled corruption and manipulation on a large scale, the 2012 parliamentary elections reinforced Ukraine's movement towards authoritarianism. The opposition was fragmented, and the Party of Regions held onto a parliamentary majority notwithstanding public discontent. The EU established an extensive range of conditions for restarting the stalled AA process following the election, including constitutional, electoral, and judicial reforms. The main issue, nevertheless, was Tymoshenko's case. Ukraine made limited efforts with the aim to maintain negotiations with the EU but opposed fundamental reforms that would weaken Yanukovych's hold on power. The agreement was finally initialised the same year.

When Ukraine came close to signing the AA in 2013, the Russian government started to exert pressure on the Ukrainian President to abandon it in favour of the Customs Union. The Kremlin’s assertive push coincided with Vladimir Putin’s return to the presidency in 2012 - he already had been president from 2000 to 2008 - and his renewed ambition to reintegrate the post-Soviet space by building a Eurasian bloc capable of rivaling the EU.

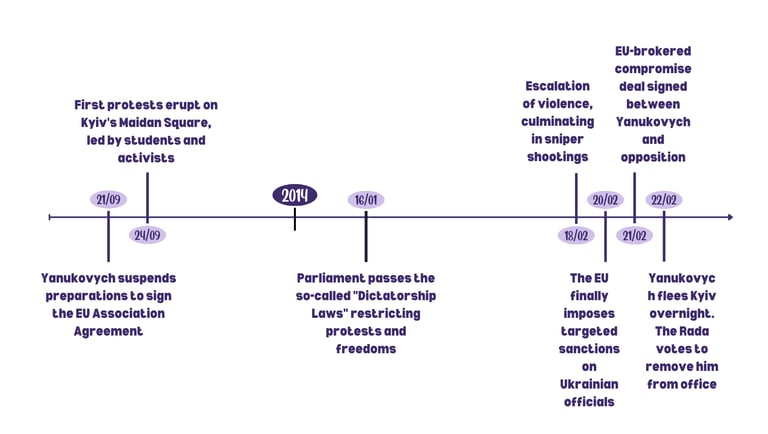

Russian pressure kept going up: Putin’s government expressed explicit and assertive opposition by imposing an embargo on certain Ukrainian goods and warning that signing the AA would be "suicidal" for Ukraine. At first, Yanukovych seemed to lean more towards EU integration, until Putin gave him a stick-or-carrot choice to make, with negative and positive measures like trade bans, custom checks, and economic incentives. Then, in November 2013, Yanukovych abruptly decided not to sign the AA - including its trade element, the DCFTA - formally suspending EU negotiations.

Contrary to that, in December, Yanukovych signed an agreement with Russia, an “Action Plan” including a $15 billion loan package and a gas price reduction of $268.50 per 1,000 cubic metres, rather than $410. Framed as economic relief to fund Ukraine’s debt, the agreement was instead directed to serve the interests of the elite - enriching Yanukovych's “Family” and appeasing the oligarchs. But this u-turn provoked a whirlwind of outrage: a geopolitical choice presented was transformed into a marker of deeper disillusion with corruption, repression, and oligarchic power. The decision to turn away from the EU in the face of Russian pressure became a mobiliser of underlying anger for democracy itself, releasing the protest movement that was to become Euromaidan.

From Suspended Accord to Mass Uprising

Yanukovych's decision to not sign the AA in November sparked a spontaneous and widespread popular uprising known as the Euromaidan or the “Revolution of Dignity”. The uprising, which quickly evolved into a broader pro-democracy mobilisation, ignited in Kyiv's Maidan Square. Unlike the 2004 protests, where electoral fraud was the main grievance, the Euromaidan protests reflected a broader societal push for (democratic) change. Mostly, it was a sense of opportunity closing that prompted mass mobilisation. Protesters, particularly the urban middle class and business interests, were reacting not just to the EU roll-back, but to years of systemic abuse and power concentration under Yanukovych. The revolutionary movement was driven by deep-rooted frustration with corruption, state violence, authoritarianism and the failure of previous political mobilisations - such as the Orange Revolution - to dismantle the oligarchic system.

Unlike the Orange Revolution, Euromaidan leveraged the power of digital technologies and social networks. Internet media, including Facebook and Twitter, helped mobilise thousands and offered alternative coverage to state-controlled media. Independent initiatives, online and offline, together with decentralised forms of self-organisation - from the Cossack-type formations to live SMS updates of sniper sightings - served both to inform and protect protesters. A notable example was Euromaidan SOS, which was a humanitarian and legal aid group; Automaidan used convoys of cars to protect protesters and patrol regime officials. Logistics were coordinated among volunteers on the square itself through channels like Spilna Sprava ("Common Cause") and provided the foundation for the self-defence units that later would develop into territorial defence battalions. Compared to 2004, when mobilisation was concentrated on a limited set of recognisable leaders and parties, Euromaidan had an inherently decentralised organisation, reflected in horizontal structures, flexible leadership, and people's legitimacy.

The movement's identity was premised on authenticity and decentralisation, with no leading representatives or ideology. Euromaidan combined peaceful protest - adequately distanced from paid counter-protests organised by the regime - and proactive confrontation. While nonviolence was dominant at first, most of the protesters grew dissatisfied with its limits, embracing bodily disobedience as state repression mounted. This not only intensified domestic polarisation but had raised the tensions with Russia. For Moscow, the growing assertiveness of the protest movement - perceived as "anti-Russian" - represented the potential collapse of Russian influence in Kyiv. In this context the Kremlin accelerated its decision to deploy the military to Crimea.

As the protest movement grew stronger, the Yanukovych regime became increasingly repressive, employing violent means. Among the primary instruments was the deployment of titushki - hired thugs used for intimidating, provoking, and physically assaulting protesters. Recruited from criminal gangs, underemployed youths, sports clubs, and off-duty police officers, these groups operated in parallel to state forces like the riot police (Berkut) but with far less discipline. and were accountable for dozens of disappearances and several deaths.

On 16 January 2014, the regime transitioned from physical to legislative repression, by passing a legislative package – known as “dictatorship laws” - to criminalise the protesters. Adopted in a rushed and non-transparent vote, the package banned activities such as wearing helmets on demonstrations, putting up protest infrastructure, or occupying roads. They also imitated Russian law by targeting NGOs that received foreign funding and suggesting restricted access to the internet. These developments backfired, with the result of intensifying public outrage rather than suppressing dissent.

The movement quickly expanded beyond Kyiv, with demonstrations erupting in western and central Ukraine. Most regional cities saw their own "Maidans". In the southeast, however, the government managed to repress resistance, managing to pre-empt a countrywide national uprising but also highlighting that there were many potential pro-Maidan supporters even in traditionally more Russia-leaning areas. The resort to violence in these regions further polarised the local populations, laying the seeds for a later divide between Maidan and anti-Maidan forces. State violence reached its peak with the deployment of snipers - likely under Yanukovych's personal control and direct Russian support - against protesters in Kyiv.

In the meantime, the extreme violence carried out by the government forces sparked international condemnation, leading the EU and the US to impose sanctions on Yanukovych's regime - even if at a very late stage. The EU eventually, after much dithering and internal struggling, agreed on the same day of the sniper shooting to impose targeted sanctions on Ukrainian leaders who used excessive force and abused human rights. These included asset freeze and visa ban, and suspension of export licences for security equipment that could be used for repression within the country. But the hesitation had been too much, as only increasing violence propelled Brussels to action. The US, meanwhile, had been pushing harder during the crisis, with more high-level sanctions already under preparation and stronger diplomatic pressure on Yanukovych and his inner circle.

On 21 February, with the facilitation of the EU, Yanukovych and the Ukrainian political opposition reached a compromise deal reinstating the 2004 Constitution and promising free and fair early presidential elections in December. Although Russia claimed that this was a binding deal, its envoy refused to sign it and Yanukovych himself seemed to have negotiated in bad faith.

While he was losing control over western Ukraine, and amid growing defections from his government, Yanukovych fled Kyiv the same night - less in fear of popular backlash than of being abandoned by his own allies. The Rada formally removed Yanukovych the following day. Although the procedure did not technically adhere to the constitutional impeachment process, the vote was practically unanimous across all factions. Oleksandr Turchynov, a party member of Tymoshenko, was appointed acting president. Ukraine's newly formed government scheduled new presidential elections for 25 May.

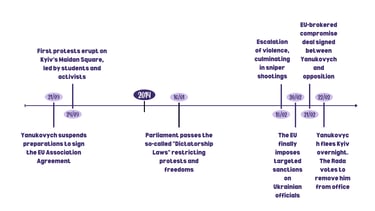

Figure 1: Timeline of Key Events Leading to Euromaidan

Post-Maidan

Russia's Military Intervention: Crimea, Donbas, and the Geopolitical Shock

As already mentioned in the first section of the article, the Kremlin was opposed to Ukraine's integration into Western structures, as this was perceived to undermine Russia's strategic position. Russia regarded the promotion of democracy by the EU and the European Neighbourhood Policy (ENP) as a direct challenge to its influence in the post-Soviet region. Following the Euromaidan uprising, Russian pressure escalated in intensity, underlining once again the geopolitical stakes of Ukraine's European integration efforts.

Russia acted fast to take control over Crimea, using special forces and riding local pro-Russian sentiment. The Kremlin rhetoric depicted widespread popular support for reunification with Russia, but Crimea, in addition to a broad ethnic Russian majority, had also Ukrainian and Crimean Tatar minorities that opposed Russia's moves. The March 2014 referendum - held under military occupation - reported near-unanimity to join Russia, but independent sources suggested far weaker turnout and support, especially among Crimean Tatars, who boycotted the vote.

The annexation, which violated international law, was made possible not just through military force, but also through disinformation and propaganda to justify the intervention. Despite a largely passive Ukrainian military presence on the ground, there was no outburst of armed violence. Repression followed directly, however: pro-Ukrainian activists were kidnapped, Crimean Tatar leaders ostracised, and Russian language replaced Ukrainian one in public life. Local pluralism was silenced and Crimea's internal ethnic and political divisions were reinforced.

In the meantime, violent conflicts had sparked in Luhansk and Donetsk oblasts, the part of Ukraine also known as Donbas, though the nature of Russia’s intervention there differed starkly from the swift occupation in Crimea. While Donbas had a large Russian-speaking population, few supported unification with Russia or separation. But most did not trust the post-Maidan authorities. And this was what Moscow exploited, together with the chaos of political transition, not any actual discrimination of Russian and Russian-speakers in East Ukraine. Still, Russia claimed otherwise. Putin alleged that Russians in Ukraine were suffering from “attempts to deprive [them] of their historical memory, even of their language, and to subject them to forced assimilation”. These claims were not distorting reality - the 2012 language law had expanded Russian-language rights, but they proved effective in justifying intervention to a domestic audience and sowing fear in eastern Ukraine.

By using this pretext, Russia launched a hybrid campaign which employed propaganda, local proxies, covert operatives, and special forces - very different from the covert and rapid conquest of Crimea by "little green men". Russia coordinated the seizure of government buildings in early April. This bolstered local militants - most of them having ties to organized crime or ex-security forces - into uprising, and discouraged a sufficient response by Ukraine, which feared provoking a full-scale Russian invasion. Russian propaganda also gained ground, returning to the old stigma of Ukrainian "fascists" against Russian speakers and providing again a pretext for interference. Russia’s disinformation campaigns aimed at discrediting pro-European protesters and framing the protests as destabilising in the region - the same method employed during the Orange Revolution.

This strategy involved a holistic media sabotage campaign, blending TV dominance, internet manipulation, and narrative warfare. In Crimea, one of the first moves after the occupation was to create a Russian television monopoly, media control being nearly as definitive as military control. Abroad, state media like Russia Today (now rebranded as RT), the world's largest supplier of news clips on YouTube at the time, flooded social and old media with content depicting Ukraine's post-Maidan as a Western coup. A new 'bloggers' law' enacted in 2014 allowed Moscow to extend censorship laws to popular online pages, muzzling critical voices and consolidating digital propaganda.

This war of information relied on manipulation and invention: for instance, archival footage from Kosovo or even films were shown as evidence of "fascist violence" or refugee exoduses. The message from the state was spread by a coordinated "troll army" of bloggers, paid commenters, and fake social media personalities, many of whom were present on Twitter, Facebook, and VKontakte (which had recently fallen into Kremlin-friendly ownership). The campaign was initially successful - especially among Russian speakers in the east and south of Ukraine - because it played on real fears and historical grievances, manipulating facts to lend credibility to a preconceived narrative.

Russia started supporting separatist movements in Donetsk and Luhansk, with the aim of securing control over the region and possibly forestalling Ukraine's westward trajectory. In a series of flash events, Donetsk and Luhansk descended into violent conflict, in contrast to the rest of Ukraine, where local elites resisted Russian-backed takeovers. In early May, the separatists conducted referendums in Luhansk and Donetsk in dubious circumstances and ridiculous turnout figures. The polls showed massive endorsements of independence, but the majority of their rivals simply boycotted them. Kyiv's military efforts suffered from poor leadership, desertions and infiltration by Russian agents.

Negotiations began in May and June, but the crisis went out of hand when pro-Russian militias shot down Malaysia Airlines MH17 in July 2014 and killed 298 civilians. International outrage sparked and the EU followed the U.S. in imposing additional sanctions. But Russian intelligence officers, volunteers, and army veterans continued to cross Ukraine. Ukraine tried to re-establish governmental control over Eastern Ukraine, and almost seemed to win over the militias in August 2014, but Russia then answered by launching a limited conventional war, effectively leading to the control of major parts of the two oblasts. Under pressure, President Poroshenko agreed to a ceasefire on 5 September. The Minsk agreements (Minsk I, September 2014 and Minsk II, February 2015) favored Russia and its proxies and made the prospects of a lasting peace questionable, impeding an actual resolution to the conflict. Hostilities persisted, even if with reduced intensity, resulting in the de facto freezing of the conflict and the laying of the grounds for Russia's future pretexts for an invasion in 2022.

The Minsk agreements were negotiated with France, Germany, and the OSCE, and by Ukraine, Russia, and separatist representatives. The agreements rested on four pillars. First, a security deal envisaged an OSCE-monitoring ceasefire, pulling out heavy weapons, and the withdrawal of foreign fighters. Second, they concerned humanitarian matters like prisoner swaps, humanitarian access, and demining. Third, there was an economic aspect which required the restoration of socio-economic links along the contact line and reconstruction of Donbas. Finally, the most debatable matter was political settlements, i.e., regional elections, constitutional decentralisation, a special self-governance status for Donetsk and Luhansk, and a general amnesty.

Though very controversial, the Minsk agreements had two great merits. They formally accepted Russia's pledge of support for Ukraine's territorial integrity by placing the reintegration of Donbas within Ukrainian sovereignty, and they assisted in lowering violence and casualties even if ceasefires remained fragile. More broadly, the agreements brought the war into a diplomatic ambit so that the EU (with France and Germany) could become a pivotal player alongside Russia and Ukraine - sidelining the United States. Still, beneath official consensus, Kyiv and Moscow had radically differing conceptions of the agreements. This tension would eventually hinder the implementation process and cast doubts on whether Minsk was a road map or a trap - an issue we explore in the next section.

Stabilisation and the EU Association Agreement

Following Yanukovych's ousting, presidential elections in Ukraine took place on 25 May 2014. Despite the difficult conditions, 60.3% turned out to vote, though fighting in the Donbas significantly impeded voting there - Crimea was excluded entirely. Billionaire businessman and former minister Petro Poroshenko, who openly supported the Maidan cause, won in the first round with a decisive victory.

While another oligarch as potential president seemed problematic, he was seen as the most viable option. Electors probably voted for him tactically to avoid a delayed second round amid growing instability. The vote disproved Russian propaganda of a far-right coup: radical nationalist parties had little support. By contrast, Poroshenko's wide electoral base stood out: he was ahead in all regions, including some in the east and south. This marked a break from the traditional regional polarisation that had shaped Ukrainian politics for over a decade.

Ukraine moved quickly to reaffirm its European path. Following Yanukovych’s ousting in March, the political provisions of the Association Agreement were signed by Ukraine’s acting prime minister, Arseniy Yatsenyuk. These were followed by the economic provisions, including the Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Area (DCFTA), on 26 June 2014, under the leadership of Poroshenko. The signing of the AA was an important milestone, marking the formal realisation of the pact that triggered Euromaidan. The EU pledged €11 billion for seven years, to be supplemented by European Investment Bank, European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, and other institutions' funds, to support a transformation of long-standing continuity rather than provide short-term relief.

Simultaneously, Ukraine moved forward towards constitutional reforms. But the 2004 Orange constitution, which had been restored during Euromaidan, created new instability among the president, the parliament, and the prime minister, eventually leading to the collapse of the ruling coalition in July. New parliamentary elections were scheduled in October.

The final step of the new agreement with the EU came on 16 September, when both the European Parliament and the Ukrainian Parliament ratified the AA simultaneously. The agreement stipulated explicit timeframes for the harmonisation of Ukrainian legislation with relevant EU legislation, ranging from two to ten years following the agreement's entry into force. By providing strategic guidance for systematic socio-economic reform in Ukraine, it represented a significant milestone in the history of Ukraine, as well as in the context of international legal documents and agreements between the EU and third countries.

During this period, the EU provided financial and reform assistance to Ukraine to assist the country's stabilisation and democratic development. The EU’s support was contingent upon progress in areas such as anti-corruption, public administration, and judicial reforms. These endeavours supported Ukraine's resolute commitment to pursuing European integration, notwithstanding the presence of both domestic and external impediments. The EU–Ukraine AA entered fully into force on 1st September 2017, after a long period of ratification.

With the EU's financial and political support, Ukraine embarked on an ambitious journey of reforms. After adopting the necessary legislation in 2014, 2015 saw the birth of three new anticorruption institutions: the National Anti-Corruption Bureau (NABU), the Specialized Anti-Corruption Prosecutor's Office (SAPO), and the National Agency on Corruption Prevention (NACP). These agencies were created through open competition procedures, consulting with civil society and international experts. Another milestone was the launch of a comprehensive e-declaration system for civil servants, for the first time making asset declarations compulsory and publicly available, unveiling the staggering wealth of many officeholders. At the same time, Ukraine the ProZorro platform of public procurements was created. This web-based platform met the requirements of the public procurement agreement with the WTO, which Ukraine joined in May 2016. Judicial reform also breached with constitutional reforms in 2016 to reduce political meddling in courts and set new norms for judicial integrity. Together, these first steps laid the ground for Ukraine's post-Maidan reform path toward eliminating the elite impunity culture.

Post-Maidan Westward Realignment

The Euromaidan revolution played a role in the weakening of pro-Russian political forces and the disaffiliation of millions of pro-Russian voters in Crimea and Donbas from Ukrainian elections, resulting in a realignment of political forces in favour of pro-Western interests.

On one hand, following Yanukovych's escape, the Party of Regions - under his leadership - experienced a fragmentation of its ranks. Many prominent leaders moved to Russia or Russian-controlled territory, including the Prime Minister and the Defence Minister, and a significant number of key figures defected, joining Russian parties. In 2015, the Communist Party was banned. Since these political forces played a pivotal role in preserving Ukraine's pro-Russian vectors, their fragmentation shifted the internal compass in favour of pro-Western forces.

On the other hand, a major consequence of Russia's military intervention was the exclusion of around 3.5 millions of voters from occupied Crimea and Donbas during the May presidential elections, as those regions had proclaimed themselves autonomous after the February revolution - although they were not recognised as such by Ukraine. These regions had previously been strongholds of parties favouring closer ties with Russia - namely the PoR and the Communist Party - so the exclusion of these voters resulted in a shift in electoral turnout, favouring pro-Western parties and accelerating Ukraine's geopolitical realignment.

After Yanujovych’s victory in 2010, the Verkhovna Rada had adopted a foreign policy resolution that preserved the goal of EU integration but renounced the one about NATO, reflecting Ukraine’s renewed balancing strategy between East and West. In 2014, the Rada reintroduced NATO accession as a national objective, marking a definitive break with the old multivector foreign policy.

While Russia's coercive measures have been effective in the short term in restraining EU integration by severely undermining Ukraine's sovereignty, these ultimately backfired. By relying on pressure tactics like embargos and energy blackmails, Moscow alienated its neighbour. Russia was unable to persuade Kyiv to join the Eurasian Customs Union, nor did it manage to gain control over Ukraine’s energy infrastructure. With the Minsk agreement, the Kremlin managed to delay the implementation of some parts of the DCFTA but at the cost of fuelling anti-Russian sentiment and ruining bilateral relations with both Ukraine and the EU. Russia's destabilisation policy undercut its own Eurasian integration project by eroding trust and legitimacy with its partners. Let’s not forget that, in 2014, AAs and and DCFTAs were concluded not only with Ukraine, but also with Georgia and Moldova.

As a result, Russia’s approach 2014 brought about a "rally around the flag" effect in Ukraine, consolidating national cohesion and lowering domestic appeal of renewed multivectorism. Most conventional political forces joined a pro-European trajectory, leading, as an example, to the establishment of "Eurooptimists" in 2015, an alliance of party-crossing deputies committed to implementing the AA. But already in the months following the Euromaidan, a majoritarian parliamentary support for the DCFTA clearly signaled that abandoning Russia was no longer a marginal position but the new benchmarks of legitimacy in Ukrainian politics. Joining Europe had become the only politically feasible option.

The 2014 illegal annexation of Crimea and the support to Eastern Ukraine separatists by Russia marked a turning point in the already fragile EU-Russia relationship. While Russia regarded the EU's presence in the region in zero-sum terms, the EU failed to recognise the implications of its policies, insisting on principles that Moscow found unacceptable.

Post-Maidan developments surprised the EU, which failed to adequately predict Russia's reaction to its growing influence in the region and was unprepared for the subsequent geopolitical context. The EU's shortcomings were a lack of strategic foresight and an inability to anticipate negative scenarios. Scholars argue that the EU's approach to its Eastern neighbourhood was characterised by an unwillingness to engage in traditional power politics, leading to a specific blind spot in dealing with Russia. This "sleepwalking" approach resulted in the EU being drawn into deeper commitments within the region without a clear long-term strategy.

EU policies were driven more by competing regional interests than by a unified vision. Yet, despite its initial lack of preparedness, the EU demonstrated a higher level of effectiveness than anticipated. Notwithstanding EU member states’ different national reactions, they took a unified stance on which actions the EU should take. European countries maintained internal unity by imposing sanctions on Russia and providing both economic and political support to Ukraine. The EU suspended high-level engagements with the Kremlin and, on 18 March 2014, adopted an initial tranche of sanctions, including asset freezes and visa bans targeting 21 Russian and Crimean officials.

This was a reluctant but landmark step that united EU member states. Germany, France, and the UK had different opinions at first: Germany needed to defend economic ties, France wanted to keep diplomatic channels open, and the UK wished for a particularly tough stance regarding financial sanctions. These were later put on hold, leaving the imposition of harder and blanket sanctions in the following months which dramatically reduced the EU's interdependence with Russia. While confrontational engagement was avoided, ties entered a state of ongoing confrontation, which was marked by distrust, stalled talks, and disengagement. Meanwhile, most of Donbas and Crimea remained under Russian control, and the Minsk agreements, which were more favourable to Russian interests, locked Ukraine and Russia into a political stalemate.

European Identity and Public Opinion Realignment

These events shaped Ukraine's European identity, which had always been a contested issue. Before 2004, perceptions of the EU were mainly geopolitical, with value-based perspectives gradually assuming a more prominent role. The European identity discourse was very fragmented, with no consensus on Europe's vision of Ukraine or the country's place within Europe. After 2004, although the European identity discourse remained contentious, it increasingly lent towards a more pro-European identity.

The Orange Revolution marked a turning point in Ukraine’s contested European identity. Before 2004, perceptions of the EU were mostly geopolitical, with values playing a secondary role. After the revolution, the discourse remained divided, but a significant shift occurred: pro-European identity narratives gained strength, gradually redefining Ukraine’s sense of belonging. While both pro-and anti-European elements were reinforced, choosing Russia as a main ally disappeared from mainstream debate, leading to a further shift in the balance of contestation in favour of the pro-European identity.

Then, the Euromaidan protests - including the painful experience of indiscriminate violence by the government - and the Russian aggression, coupled with the political and electoral shifts aforementioned, strengthened Ukraine's distinct identity, separating it from Russia's sphere of influence. In contrast with Russia's largely pragmatic approach – based on security issues, energy dependence, or trade - the EU relied on normative attraction, for which European integration was explained as a civilisational project founded on shared values such as democracy, rights, and human dignity. It is no coincidence that the 2014 "revolution of dignity" adopted the name "Euro-Maidan" to signal the country’s commitment to European identity.

More specifically, before 2014 Ukrainian politicians already used to frame European integration in terms of economic benefits but also political values. The Euromaidan protests reinforced the growing alignment with European values, particularly democracy, human rights, and good governance, which were becoming increasingly prevalent in Ukrainian society. Moreover, the European identity discourse evolved, with the focus shifting towards a civilisational and vital choice that underlined Ukraine’s need for full political and cultural autonomy from Russia. The prevailing political discourse positioned Ukraine as a defender of European values in the face of Russian aggression, thereby reinforcing a long-term pro-Western orientation and providing less space for the previously favoured pragmatic strategy vis-a-vis Russia.

Consequently, European identity, in addition to economic and political incentives, played a crucial role in shaping Ukraine's foreign policy preferences. The violent suppression of protests and Russia's occupation of the Ukrainian territory profoundly changed Ukrainians' perceptions of external powers, shifting elite narratives toward a foundational framing of Ukraine's foreign policy. Support for close ties with Russia declined significantly, and Ukraine's pro-Western orientation stabilised. Support for NATO and the EU increased dramatically after 2014, stabilising as the dominant foreign policy preference among Ukrainians. In fact, Ukrainians started to see NATO as a safeguard against Russian imperialism and as a guarantee of peace and security. Concurrently, trust in Russia declined sharply. This shift in attitude helped legitimise pro-Western forces, further marginalising pro-Russian perspectives.

Importantly, civil society and internal actors did not expect top-down reforms: they stepped into the foreground as the main agents of change in the post-Maidan transition. New institutions such as the anti-corruption institutions emerged as a direct reaction to popular calls for responsibility, and were in fact designed through increased civic society involvement. Mechanisms like the ProZorro electronic procurement system and open data policy brought new transparency to public funds, empowering the public as well as better monitoring politics. These early achievements represented the consolidation of post-Maidan Ukrainian identity, increasingly bound to EU standards and practices, and driven by a population committed to rebuilding governance from below.

The delicate balance between Russia and the West that characterised much of Ukraine's early foreign policy has been made increasingly irreversible by the events that occurred in 2014. The institutionalisation of Ukraine's European identity in 2014 was not merely rhetorical or institutional - it became enshrined in political practice and public opinion expectations. The events of 2014 established the momentum that would eventually guide Ukraine's application to join the EU. EU candidate status in 2022 and Ukraine's close identification with the Euro-Atlantic frameworks after the full-scale Russian invasion are in many respects the pinnacle of these policy and identity shifts. The next section will explain how the war after 2022 solidified this course and accelerated the process of Ukraine becoming a contested neighbour turned aspiring EU member state.

Conclusion: Disillusionment and the Road to Renewal

The hopes born through the Orange Revolution had rested on the potential that Ukraine could move toward democratic progress, prosperity, and European integration. The succeeding decade uncovered the structural weakness of this vision. Factionalism in Orange leadership, loss of popular trust, and lack of sustained attempts at reform created disillusionment and political gridlock. The EU, on the other hand, could not counter this initial symbolic turn westward with a compelling and transformative offer. The Eastern Partnership, more visionary than ENP, was still not well-oriented to overcome Ukraine’s institutional and geopolitical constraints. As a result, the promise of "Europeanisation" became increasingly illusory, plagued by stalled reforms and selective engagement, and dependent on external vulnerabilities.

Russia capitalised on this vacuum. The suspension of the AA in 2013 signified the collapse of Ukraine's multivector strategy and the erosion of the post-Orange consensus. Euromaidan emerged against such a context not so much as a reaction to a presumably corrupt president, but a reaction to the fact that Ukraine could no longer be politically and institutionally ambiguous. The annexation of Crimea and war in Donbas signaled an irreversible rupture which, ironically, also presented new bases for political consolidation. The Russian response to Euromaidan pushed Ukraine to accelerate reforms and redefine itself in European terms not as utopian visions, but as survival necessities. Europeanisation was no longer technocratic alignment for most Ukrainians: it became existential.

And it required a recalibration on behalf of the EU. Blamed for years for strategic ambiguity and performative engagement, Brussels at last recognised the cost of its half-hearted policy. The path that led to the grant of candidate status in 2022 was both a geopolitical gesture against Russia's full-scale invasion and a realisation that Ukraine's European destination could no longer be dubious. The gap between rhetoric and substance was bridged, at least in part, on each side for the first time. As the third and final section will show, the road to membership is still complex. But for the first time since independence, Ukraine and the EU appeared to be willing - and compelled by events – to walk it together, with higher stakes and stronger commitments than ever.

Alexandrova-Arbatova, N. (2016, March 23). A Russian view on the Eastern Partnership. Clingendael Institute. https://www.clingendael.org/publication/russian-view-eastern-partnership

BBC NEWS (2005, September 8). Ukraine leader sacks government. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/europe/4225566.stm

Bosse, G. (2019). Ten years of the Eastern Partnership: What role for the EU as a promoter of democracy?. European View. 18. Wilfried Martens Centre for European Studies. https://doi.org/10.1177/1781685819887894

Council of the EU (2014, February 20). Foreign Affairs Council - Ukraine: EU agrees on targeted sanctions. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/meetings/fac/2014/02/20/

Council of the EU (2014, March 7). Council Regulation (EU) No 269/2014 of 17 March 2014 concerning restrictive measures in respect of actions undermining or threatening the territorial integrity, sovereignty and independence of Ukraine. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32014R0269

D’Anieri, P. (2006). Explaining the success and failure of post-communist revolutions. Communist and Post-Communist Studies, 39(3), 331–350. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.postcomstud.2006.06.002

D'anieri, P. (2007). Understanding Ukrainian Politics: Power, Politics, and Institutional design: Power, Politics, and Institutional design. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315698489

Delcour, L. (2017, December 19). Dealing with the elephant in the room: the EU, its ‘Eastern neighbourhood’ and Russia. Contemporary Politics, 24(1), 14–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/13569775.2017.1408169

Delcour, L., & Wolczuk, K. (2015). Spoiler or facilitator of democratization?: Russia’s role in Georgia and Ukraine. Democratization, 22(3), 459–478. https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2014.996135