Article / What can we learn a year after the 2024 European elections?

Introduction

A year has passed since the 2024 European elections last June. In the first part, written just a month after the elections, the rise of the right-wing parties was captured, highlighting the potential impact of this shift on European Union's (EU) policy priorities, internal cohesion, and democratic legitimacy, thus marking a significant turning point in the EU's political landscape. But at the time, it was too early to assess how this reconfiguration would play out across European institutions and Member States. Twelve months later, speculation based on the provisional results has given way to observable trends. So, we return now with a clearer picture, not just of who governs and how, but of the patterns and consequences shaping the future of the Union.

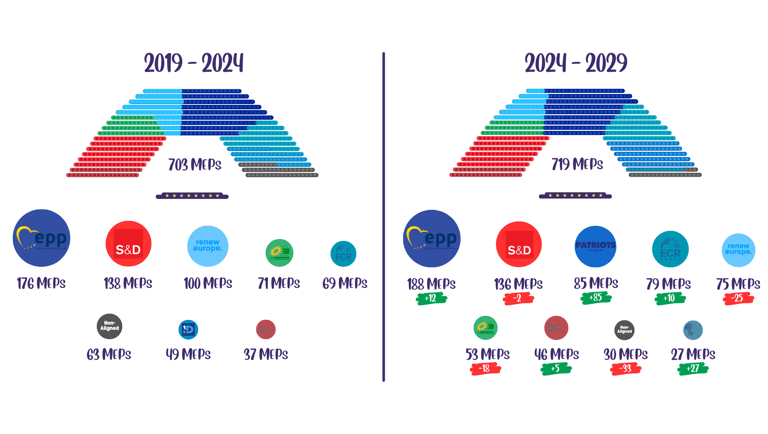

Over the past year, right-wing forces have been powerful not only in national capitals or in political debates, but also at the heart of the EU institutions themselves. Indeed, the European Parliament (EP) has undergone a historic realignment. The new far-right, sovereigntist group “Patriots for Europe” (PfE), led by France's Rassemblement National and Hungary's Fidesz, is now the third largest force behind the European People’s Party (EPP) and the Socials and Democrats (S&D), upsetting the traditional balance of power. Together with the emergence of the new “Europe of Sovereign Nations” (ESN) bloc, this shift to the right has caused previous alliances to crumble, as the fall of the Identity & Democracy (ID) group and the erosion of European Conservatives and Reformist (ECR), Renew Europe and the Greens show. While these changes embody the Parliament's new ideological poles, they illustrate a deeper structural shift that is leading to conservative and nationalist groups seeking to redefine the values of the EU. As noted in a joint report by the European Council on Foreign Relations and the European Cultural Foundation, there is increasing adoption of an exclusionary, ethnically based concept of “Europeanness”. This directly undermines the values that are historically anchored in the European project, namely universalism, equality and secularism. Meanwhile, despite the remarkable increase in youth participation in the 2024 elections, in which far-right parties enjoyed unprecedented electoral support among young voters (among others), young people remain systematically underrepresented in European politics and largely excluded from major decision-making roles . Another broader disruption is the intensification of polarisation within the EP, making legislative negotiations more complex. Since/Starting from the June 2024 elections, the traditional centrist consensus has been challenged by cooperation between the center-right and far-right political groups. For example, EPP leader Manfred Weber has come under fire from his centrist partners for undermining the originally agreed ‘pro-European’ coalition of EPP, S&D, Renew Europe and the Greens by forging tactical alliances with the far-right PfE and ECR groups.

Signalling a significant ideological shift, already influencing the EU's agenda, foreign policy stance and internal cohesion, these developments mean more than a mere redistribution of seats. The consequences of this realignment, unfolding along three major trends, are real. First, there is an increasing transatlantic drift. Second, the EU is experiencing a “greenlash”, a broad backlash against climate policy fueled by rural discontent and the drive for European competitiveness. Thirdly, the Union is facing a growing democratic backslide. Rule-of-law norms, pluralism and civic freedoms are increasingly eroded both in the Member States and within the EU institutions themselves. So, how the rise of the right on the ground has been reflected in the materialisation of these three trends shaping the future of the European Union.

Reconfiguring Power in the European Parliament

The New Parliamentary Arithmetic

Led by the French Rassemblement National (RN) under the leadership of Jordan Bardella and the Hungarian Fidesz under the leadership of Viktor Orbán, the PfE was officially founded in July 2024 following the collapse of the ID group. The appeal of the PfE, which attracted numerous parties at its inception, such as the Italian La Lega, the Spanish Vox, the Portuguese Chega, the Danish People's Party, the Austrian FPÖ, the Finnish Finns Party, the Czech ANO and the Dutch PVV, was based on several factors. Given the instability and marginalization of the ID and the weak cohesion of NI members, many nationalist parties were disillusioned with the fragmented far-right landscape in parliament. Perceiving that the PfE is better organized, more diplomatically acceptable and able to negotiate influence in committees and leadership positions, especially based on the personal political capital of Orbán (as an experienced head of government) and Bardella (as a rising star of the far right in France), several parties previously affiliated with the ID chose the PfE instead, which provided a platform to promote Euroscepticism, national sovereignty, anti-immigration policies and opposition to EU federalism.

However, not all members joined the PfE, such as the German Alternative for Germany (AfD), the Bulgarian Wasraschdane, the Polish Konfederacja, the Spanish Se Acabó la Fiesta and other dissidents from the NI or the radical right. The remaining core of ID members and non-affiliated far-right parties, who either rejected the leadership of the PfE or were excluded for ideological or reputational reasons, together formed the ENS group. The AfD is one such example, as it was excluded from the other groups due to its extreme rhetoric, internal scandals and poor image in mainstream European politics. In terms of ideological divergences, the PfE aims to reshape the EU from within, while the ESN includes parties that advocate hard Euroscepticism or even EU exit strategies and even break off relations with NATO or openly support Russia, which is too radical even for the PfE's sovereigntist platform.

The dual emergence of PfE and ESN was thus the result of deliberate political planning and strategic coordination between national leaders seeking greater influence in Brussels and marked a decisive realignment of the European far right, transforming previously fragmented nationalist forces into coherent parliamentary actors. Despite internal differences, both groups work informally with the ECR and occasionally receive support from NI members, giving them disproportionate influence, especially when centrist blocs are divided.

Unstable Blocs and Tactical Politics

The rise of the far right, in particular the formation of the PfE and ESN, has confirmed a seismic shift in the composition of the European Parliament, fundamentally redrawing internal parliamentary balances. With PfE now the third largest group at 84 seats, behind the EPP (188 seats) and the S&D (136 seats), the direction of the Parliament is no longer controlled by the EPP, although it is still the dominant force. During the previous Parliament (2019-2024), the so-called “Ursula majority”, the informal pro-European alliance of the EPP, S&D, Renew and often the Greens, provided the working majority (361 out of 720 MEPs). While that majority still technically exists (401 seats), it is increasingly unstable, especially on contentious issues such as migration, climate and defense, which spark internal fractures. In contrast, the EPP, ECR and PfE fall just short of an absolute majority, but could turn the tide with the support of NI or ESN. The most consequential development of this new arithmetic, however, is the formation of a potential blocking minority of the extreme and hard right. With 240 MEPs required to obstruct or delay controversial legislation, a coordinated alliance of PfE, ESN, ECR and NI could wield significant veto power with around 20 to 30 additional votes, possibly from EPP dissenters.

Figure 1: Composition of the European Parliament in 2019-2024 vs. 2024-2029 by political group

Source: European Parliament

Behind this arithmetic, however, lies a deeper ideological fragmentation: if the center is fragmented, the right is not united either. Renew Europe, for example, is weakened and internally divided, with French Renaissance MEPs adopting more conservative positions on industrial policy, defence, and foreign affairs and aligning with the EPP in parliamentary votes and committee work . By contrast, Dutch (e.g., D66) and Nordic liberals (e.g., Danish Venstre, Swedish Svenska Liberalerna), are leaning towards the Greens and the S&D, particularly on issues like climate action, civil liberties, and rule-of-law enforcement. Meanwhile, the S&D, though still rhetorically cohesive, is struggling to find a balance between progressive agendas and national interests, particularly between German SPD MEPs who support defence integration and southern delegations (e.g., Spanish PSOE, Italian PD) who are sceptical of militarization or fiscal expansion . Even the EPP is internally divided, between Manfred Weber's push to the right on ECR and PfE and more traditional pro-European groups such as the Portuguese PSD or the Irish Fine Gael, which remain committed to centrist cooperation and the enforcement of the rule of law . The right is also ideologically diverse and acts opportunistically, encompassing Atlanticists such as Vox, pro-Russian voices such as Fidesz, strong supporters of EU coordination such as ANO and other parties that lack strategic coherence or legislative discipline .

The result of this fragmented landscape is a Parliament in which coalition-building is no longer formed through stable programmatic alliances, but from dossier to dossier. The outcome is a Parliament that may be rhetorically stronger, but that is weaker in agenda-setting and more prone to internal volatility. This unpredictability of the new institutional configuration is not only capable of twists and turns, but has already impacted three key policy areas: defense and transatlantic relations, climate policy and democratic governance. This reflects a Europe in transition, caught between polarizing forces and struggling to maintain institutional cohesion.

Transatlantic Relations and European Rearmament

Transatlantic Drift: Trump's Electoral Shock

The opening of the 2024-2029 EP mandate coincided with the re-election of Donald Trump as President of the United States in November 2024, a major geopolitical turning point in transatlantic relations. Trump’s return to the White House prompted a realignment of U.S. policy on the war in Ukraine and reignited trade tensions with the EU, hence spurring European leaders to intensify their push for strategic autonomy, especially in the defence sector.

Such damage had largely been anticipated by analyst, who warned that Trump was “bullying democratic leaders... and propping up autocrats”, and predicting that “a second Trump term would have meant further erosion of American democracy and the postwar liberal order”. Those concerns materialised quickly in Brussels. For instance, the EP plenary debates of November 13, 2024 and January 21, 2025 revealed deep divisions among MEPs regarding how the EU should respond to the new U.S. administration.

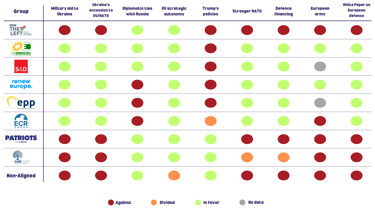

A bloc consisting of The Left, The Greens, S&D and Renew saw Trump's victory as a threat to democratic norms, transatlantic solidarity and global stability. They also expressed concern about the American withdrawal from Ukraine, the rise of economic nationalism and the weakening of NATO. In response, these groups emphasized in their plenary speeches the importance of defending European values, strengthening multilateralism and preparing collectively for the coming US unilateral turn. Conversely, a more pragmatic tone emerged from the EPP, Renew, and ECR, which underscored the need to reinforce European defence capabilities while maintaining the transatlantic alliance, even under Trump. In this context, where a rupture with Washington must be avoided, European rearmament was framed as a means of restoring parity and respect within the partnership, rather than replacing NATO. The far right, with PfE and ESN, however, openly celebrated Trump’s return, calling for a "Europe First" in the image of Trump's "America First". By invoking slogans like “Make Europe Great Again”, “We need our own Trump”, “Trump will save the West” during plenary debates, these groups revealed their admiration for Trump’s nationalist model and their rejection of EU federalism and multilateralism, in contrast to the vision of a united and autonomous Europe as advocated by pro-European parties.

Trump's re-election has thus highlighted, if not intensified, an internal polarization within the EU. On the one hand, progressive and multilateralist groups are calling for a united, autonomous and responsible Europe, and see Trump’s return to power as a threat to the Union’s democratic values. On the other hand, Trumpist sovereigntists want to weaken the role of European institutions and restore national sovereignty, while recognizing Trump as an ally.

Yet despite these ideological divides, a rare consensus has emerged: Europe can no longer rely on the United States, the latter currently seen as “unstable”. Although the motivations vary (e.g., emancipation over American influence, self-defense, global actor as key peace promoter), the need for credible European strategic autonomy became clear. In fact, all political groups, from the left to the right, recognized the urgent need to improve the EU's defence capabilities and reduce its dependence, to some extent. For example, the Greens, the S&D, Renew, the EPP and the ECR stressed the urgency of developing an autonomous European defense capability that plays a complementary role to NATO so that the Union is able to defend itself.

This vision has only been reinforced because of Trump’s early provocative actions and policies as president, which did not spare the EU. His administration adopted an erratic stance toward Ukraine. On February 28, 2025, for instance, the U.S. President displayed a harsh attitude towards Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky when the two met at the White House, ultimately resulting in the cancellation of a press conference and the suspension of an agreement on mining resources. Trump, who claimed to quickly resolve the war in Ukraine, has in reality adopted an ultimately contradictory attitude. He would support Ukraine but regularly criticize its president and demand territorial concessions, notably on Crimea; while he would also send contradictory signals to Russia, denouncing certain attacks while maintaining an ambivalent posture. Another source of tensions concerns NATO, which he reignited by threatening U.S. disengagement unless member states raised defence spending to 5% of GDP, more than double the current budget. Economically, the American President also relaunched a global trade offensive, introducing 25% tariffs on steel and aluminum against the EU in February 2025 because of practices he deems “unfair”. This was followed by 20% duties on most European products in key sectors (e.g., agriculture, automotive, luxury goods) as of April 2025, which he justified by citing a €183 billion EU-U.S. trade deficit by the end of 2024.

Despite fearing a new trade war that would have far-reaching consequences for European industries, the EU responded swiftly to Trump’s protectionist agenda. On February 11, 2025, a broad consensus emerged on the need to strengthen the EU's digital and technological sovereignty. Driven by a need for greater strategic autonomy and competitiveness (EPP, Renew, S&D, the Greens), the rejection of American neo-imperialism (The Left, PfE), and a desire for a balanced cooperation relationship (ECR, EPP, Renew), the EP majoritarily supported the proposed Commission retaliatory tariffs on American products (particularly in the agricultural sector) worth up to €26 billion, later extended to €44 billion. Due to be phased in from April 2025, the EU actually suspended its countermeasures, following Trump’s unilateral suspension of U.S tariffs. Although a temporary truce was reached, rensions resumed with new tariff hikes of up to 50% in May 2025, before another setback after a call with Commission President Ursula von der Leyen, justifying this roller coaster as a way to reach a rapid and balanced agreement with the EU. Simultaneously, the Parliament has pushed for diversification of EU trade relations, opening talks with India, the Philippines, and Thailand, with the aim of reducing overdependence on the U.S. market and establishing new economic ties.

Legislating Europe's Autonomy

In the wake of increasing instability, the Parliament has recognised the need to reassess its strategic orientation, both in terms of support for Ukraine and in redefining Europe’s own defence posture. This dual imperative has translated into a steady reaffirmation of political, financial, and military support for Ukraine across multiple plenary sessions between mid-2024 and early 2025, as well as the adoption of the White Paper for European Defence.

EU Positioning Towards Ukraine

Despite internal divisions, a broad parliamentary consensus has emerged around the principle of aiding Ukraine. The mainstream political groups (i.e., the Greens, S&D, Renew, EPP and ECR) have framed military support not merely as solidarity with a sovereign state under attack, but as an investment in Europe’s own security and stability. For instance, support for Ukraine was also linked to the EU’s longer-term ambition of building strategic autonomy; whether through a coordinated European defence framework (EPP and ECR), joint procurement mechanisms (Renew), or through energy and industrial independency initiatives (PfE).

But this consensus does not extend across all parties. The Left, ESN, some parts of the PfE, and some Non-Inscrits, have consistently opposed military aid. Their arguments are twofold. First, such aid risks escalating the conflict rather than resolving it. Second, it reflects a subservience to foreign, primarily American, interests. And for the far right, in particular, the EU’s involvement in Ukraine is portrayed as diverting resources away from European citizens and as a provocation that increases the continent’s vulnerability to Russian retaliation.

Such an ideological divide also informs perspectives on diplomacy and EU enlargement. The majority of MEPs (the Greens, S&D, Renew, EPP, ECR) advocate for a “victory-based peace”, asserting that sustainable peace requires a militarily empowered Ukraine, potentially leading to EU membership. In contrast, the far left and far right (the Left, ESN, some PfE, NI) insist that the war cannot be won militarily. Instead, they advocate for immediate negotiations, and remain skeptical about Ukraine’s potential accession to the EU, viewing it as both misaligned with Europe’s strategic interests and provocative towards Russia, just like NATO’s influence expansion.

Yet, despite such differences, most groups perceive the war in Ukraine as a challenge to European security, justifying a long-term military, financial and political commitment. Despite a conditional consensus running up against several political fault lines (e.g., calls for de-escalation, enhanced diplomacy, U.S. uncertainties and criticism) leading to intense debates among MEPs, decisive actions were taken. On 19 September 2024, MEPs voted overwhelmingly (425 in favour, 131 against, 63 abstentions) to lift both financial and military restrictions, such as preventing Ukraine from using Western weapons against legitimate military targets in Russia, which hinder its right to self-defence. The Parliament also reiterated the need to accelerate deliveries, called on Member States and NATO allies to commit a minimum of 0.25% of their GDP to Ukraine’s military aid, and emphasised the importance of maintaining and strengthening sanctions against Russia, Belarus, and non-EU countries providing military aid to Russia, as well as calling for stricter measures to combat the circumvention of sanctions by companies and non-EU countries. A legal mechanism for confiscating frozen Russian assets was also reaffirmed. Four weeks later, further measures followed. On 22 October 2024, the EP approved (518 in favour, 56 against, and 61 abstentions) a €35 billion exceptional loan package to Ukraine, granting exceptional macro-financial assistance to the country, partially guaranteed by frozen Russian Assets, as part of a broader G7 agreement. Disbursed until the end of 2025, the loan was made conditional upon democratic benchmarks, human rights standards, and reform commitments. Then, a month later, on 14 November 2024, the Parliament condemned the Russian “shadow fleet’, a major source of revenue for financing the war in Ukraine through the illegal export of oil to circumvent international sanctions, while re-stating the need to end imports of Russian fossil fuels and to reinforce the price cap on Russian oil, highlighting the limited impact of current sanctions while the EU continues to import Russian energy. Shortly after, on 26 November 2024, in response to intelligence reports about Chinese and North Korea support for Russia, MEPs called for heightened military assistance and intensified diplomatic pressure. Indeed, the EP urged China to cease all military support to Russia or face consequences for EU-China relations, pointed out the importance of including Ukraine in peace processes and the need for international support for Ukraine’s peace plan, and increased military assistance.

Taken together, these decisions signal a Parliament that, despite internal rifts and polarisation, remains firmly committed to Ukraine’s defence and sovereignty. As a matter of fact, Ukraine is no longer perceived as a peripheral issue, but as a strategic test for the EU’s credibility, unity, and geopolitical agency. And although disagreements persist, particularly over the methods and long-term strategy, the EP has managed to maintain cohesion on Ukraine policy in the face of external threats and domestic polarisation.

"ReArm Europe" and EU Strategic Autonomy

In parallel with its increased engagement in Ukraine, Parliament has undertaken a historic reassessment of the European security situation. Triggered in part by the re-election of Donald Trump at the end of 2024 and the volatility of transatlantic relations, it has been widely recognized that the Union must take more responsibility for its own defence, with the aim of moving from dependence on NATO to a more autonomous yet cooperative European strategic framework.

The debates in Parliament on November 14, 2024 and January 22, 2025 showed that strategic autonomy has broad support in principle, albeit not in terms of the means or the end goals. Despite the broad conceptual support, it is held back by differing interpretations. On the one hand, most centrist and pro-European political groups (Greens, S&D, Renew, EPP) argue for a European ability to act independently when needed, especially in regional crises or in the face of a US withdrawal. Their view is not anti-NATO but complementary, seeing a stronger EU as a strength rather than a source of undermining the Alliance. On the other hand, more conservative factions such as the ECR and some factions of the PfE cautiously agree with the idea of European autonomy, but only if NATO remains the anchor of European defense. The other part of the PfE, the left, the ESN and NI, on the other hand, reject strategic autonomy outright, describing it as militaristic, unaffordable and a threat to national sovereignty.

This divide was also visible in discussions on EU-level defence funding. While mainstream groups pushed for a common defence budget to fill capability gaps anc accelerate industrial readiness, the hard left and right opposed the idea. While the far right preferred national control, the left urged redirecting funding toward social investments rather than military build-up. Polarisation became even more evident during debates on the creation of a EUropean army. A minority within the Greens, S&D and Renew floated the idea of a future integrated force. Meanwhile, the EPP and ECR rejected such federalist ambitions, advocating instead for flexible coalitions, such as PESCO, and coordinated investment, and the rest were firmly opposed to any form of military integration, hence remaining committed to pacifism or sovereign doctrines.

Despite these fractures, a turning point came on 19 March 2025, when the European Commission unveiled the “ReArm Europe - Readiness 2030” plan, accompanied by a White Paper on European Defence. Outlining solutions to enhance European defence capabilities and industrial resilience through a €800 billion mobilisation, the plan outlined an ambitious agenda, including to streamline procurement and stabilise demand via coordinated EU-wide framework, support dual-use infrastructure (e.g., space communications, military mobility), prioritise key military capabilities (e.g., air and missile defence, drones and counter-drones, cyber, AI, quantum, electronic warfare, artillery systems), as well as establish EU-Ukraine defence partnerships in order to gradually integrate Ukraine into the European Defence Technological and Industrial Base. The plan also tied in with Ukraine’s defence by supplying 2 million artillery shells annually (with funding secured for 2025), enhancing air defence systems, precision missiles and drones, and training and equipping Ukrainian brigades. For the Union, this also gives the possibility to learn from the battlefield, and then inform European forces and future capability needs. In fact, with its war experience, Ukraine has become a laboratory for military innovation, which not only enables it to increase and modernize its capabilities and supply competitive products, but could also help address the weaknesses of the European defense industrial sector. The White Paper also emphasised economic sovereignty, proposing European preference in defense procurement, boosting R&D in emerging technologies, securing critical raw materials, promoting skills development and talent attraction for rapid industrialisation. The diversification of suppliers is another important point, in order to reduce dependencies and strengthen the European defence industry through partnerships expansion with key allies and like-minded partners in neighboring countries and the Indo-Pacific (from the UK and Canada to Japan and India). The EU is therefore committed to deepening this cooperation in a mutually beneficial way. To finance this initiative, the Commission proposed five pillars: a new SAFE financial instrument offering up to €150 billion in joint defence investment loans (1), the temporary activation of Stability Pact derogations to allow more defence spending (2), the optimized use of existing EU defence funds (3), the expanded role of the European Investment Bank in military projects (4), and the mobilization of private capital, particularly for SMEs and innovation (5).

Put to a vote on 11 and 12 March 2025, the proposal received a majority of 419 votes in favour, with the EPP, Renew, S&D, Greens, and a good part of ECR expressing their support for the ambitious vision, as well as their shared idea for a coordinated defense, reactive budget and autonomy. Yet, 204 MEPs, primarily from the PfE, the Left, ESN and NI, voted against it, citing fears of militarisation, sovereignty loss, or unfeasible costs. And an additional 46 MEPs abstained, reflecting broader doubts about the plans’s financial and institutional viability. This adoption marked a strategic milestone: the EU is laying the foundation for a cohesive, hybrid, and semi-autonomous defence policy, one that is capable of complementing NATO, but also stepping in when the transatlantic link falters. However, this step forward is taking place against a backdrop of fragile consensus and ideological friction. As defence becomes a central pillar of European integration, it also becomes a lighting rod for political contestation.

Table 1: European political groups' positions on transatlantic relations and European rearmament (2024-2025)

Defence Politics: National Divergences and Public Pressures

While the European institutions have taken the lead in advancing strategic autonomy, they are not alone. Across the continent, Member States and public opinion too are increasingly aligned in their concerns over Russia’s aggression and the potential collapse of the transatlantic security framework.

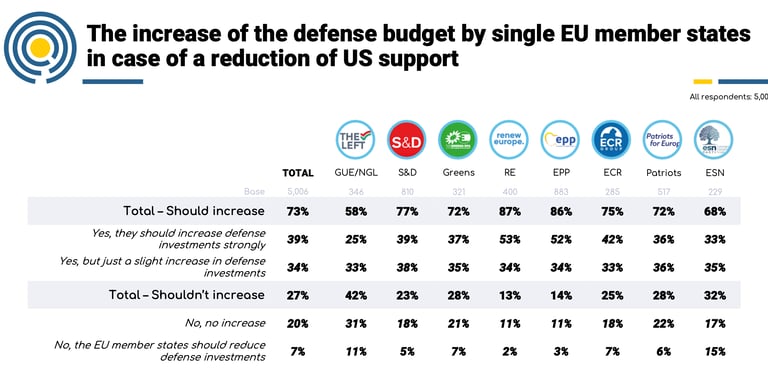

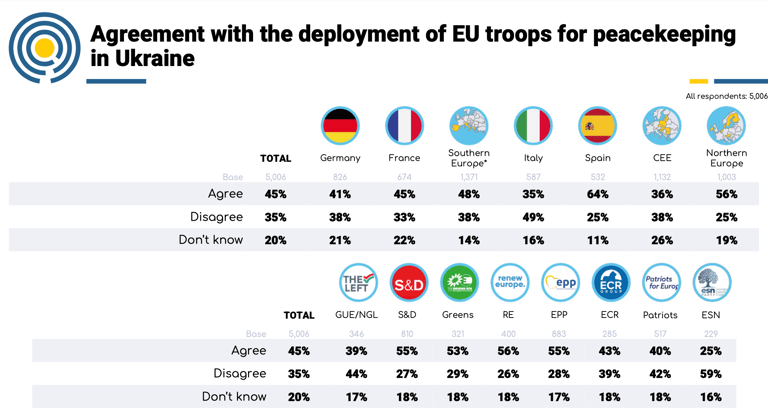

A 2025 European Commission survey found that 71% of EU citizens believe the Union should enhance its ability to produce military equipment, and 77% support a common EU defence policy. Reinforcing this, a Polling Europe Institute survey collecting responses from over 5.000 citizens across the 27 Member States revealed that three in four Europeans would support raising national defence budgets if the U.S. were to disengage from NATO. Notably, 39% favour a significant increase, and 34% a moderate one, while only 7% favour cuts. While support is strongest in Germany, France, Spain, and the Baltic and Central European countries, Italy stands out as the sole country with a majority (51%) opposing defence budget increases. By political alignment, support is highest among Renew (87%), EPP (86%), and S&D (77%) voters. Opposition is concentrated on the far left and sovereignist right, with 42% of Left voters and 32% of those affiliated with the ESN oppose higher defence spending. On the more sensitive issue of deploying EU peacekeeping troops to Ukraine in the event of a ceasefire, European citizens are more divided. While 45% support the idea, 35% oppose it, with Spain being the most supportive (64%) and Italy the most opposed (49%). Looking through the political lens, liberal, Christian Democrat, and Social Democrat voters show the strongest support (55-56%), while opposition is led by far-right sovereignists (59%), the radical left (44%), and nationalist parties such as PfE (42%).

Table 2: The increase of the defense budget by single EU member states in case of a reduction of US support

Source: Polling Europe

Table 3: Agreement with the deployment of EU troops for peacekeeping in Ukraine

Source: Polling Europe

Reactions to the Commission’s strategic defence agenda, especially the ReArm Europe plan, vary significantly between Member States, mainly driven by diverging defence priorities and financial fault lines.

As one of the leading supporters of European rearmament, Germany emerged. In May 2025, new Chancellor Friedrich Merz declared his intent to make the Bundeswehr the strongest conventional force in Europe, underlining military strength as a national priority in light of Russian threats and shifting U.S. posture. As the EU’s most populous and powerful country, this positioning is crucial. Germany must position itself as a reliable leader for its European partners and provide strong support to Ukraine. While Germany still trails Poland and France in troop numbers, it seeks to strengthen defence infrastructure and capabilities while remaining a firm NATO partner.

Likewise, France backed EU rearmament, proposing a joint EU loan mechanism to finance collective defence efforts. Although the idea received support from southern European states (e.g., Spain, Greece) and Eastern front-line countries (e.g., Finland, Poland, the Baltics), fiscally cautious countries like the Netherlands oppose the idea, citing concerns over rising EU debt, especially with COVID recovery repayments approaching in 2028. What’s more, some countries already benefit from favourable borrowing rates and are reluctant to take on more debt, while more indebted ones may face financial penalties. This debate only intensified after the March 2025 release of the White Paper on European Defence. Meanwhile, France also floated the idea of extending its nuclear deterrent to cover the EU, a move that would represent a significant political and strategic shift. France, which maintains an independent arsenal of around 290 nuclear warheads, differs from the UK (225 nuclear warheads), whose deterrent partly depends on the U.S. (The British nuclear program Trident is closely linked to the American nuclear program: the missiles were manufactured in the U.S. and then bought by the UK, they are maintained by Lockheed Martin, an American defense and security company, and certain parts, such as the warhead aeroshells, are bought from the U.S.). While potentially sending a powerful signal to Moscow, such a step also raises concerns about escalation, doctrinal ambiguity, France’s sole decision-making power on nuclear use, and the expansion of French vital interests to those of the entire Union. Moreover, despite the existence of French deterrent capabilities, we could point out the imbalance of forces compared with Russia, which has a much larger stockpile (4309 plus 1150 retired nuclear warheads).

Nonetheless, some member states are rather skeptical about the ReArm Europe plan. In Italy, for example, the Commission’s plan has been harshly criticised across the political spectrum. As Daniele Gallo, professor of EU law at Luiss University has warned, Italy’s primary concern is its high public debt: “Italy’s main risk is excessive indebtedness. Italy is already more indebted than other countries”. Though Italy is NATO’s second-largest contributor and boasts a well-equipped force of 160.000 soldiers, it remains reluctant to deepen EU military integration. Instead, Rome prefers to maintain its reliance on the transatlantic alliance and has rejected the idea of foreign deployments. At the NATO summit, Spain insisted on maintaining its commitment to spend 2.1% of its GDP on military expenditure, rather than increasing its spending to 5% of GDP. Trump responded to this decision with strong criticism, accusing Spain of taking advantage of its allies and threatening to impose tariffs on the country.

In stark contrast, Eastern and Baltic states have emerged as the vanguard of European rearmament. Feeling the most threatened by Russian expansionism, ramping up defence budgets is vital. Poland is targeting 4.7% in 2025, and building toward a 500.000 strong army. A similar trend is occuring in the Baltics, as Estonia is preparing to reach 5.4% of GDP by 2029, Latvia increased its 2025 defence budget to 3.45%, and Lithuania reached 3.9% of GDP in 2025. Together, the three Baltic countries have also launched the “Baltic Defence Line”, a 1.360km fortified barrier along the borders with Russia and Belarus, to potentially form the “North-East Border Shield,” with investments that could reach €10 billion. Thus, the Eastern flank is gradually becoming the new geographic and ideological engine of the alliance’s readiness and deterrence posture, and EU rearmament, bolstering military presence in the region, enhancing NATO’s readiness and deterrence posture.

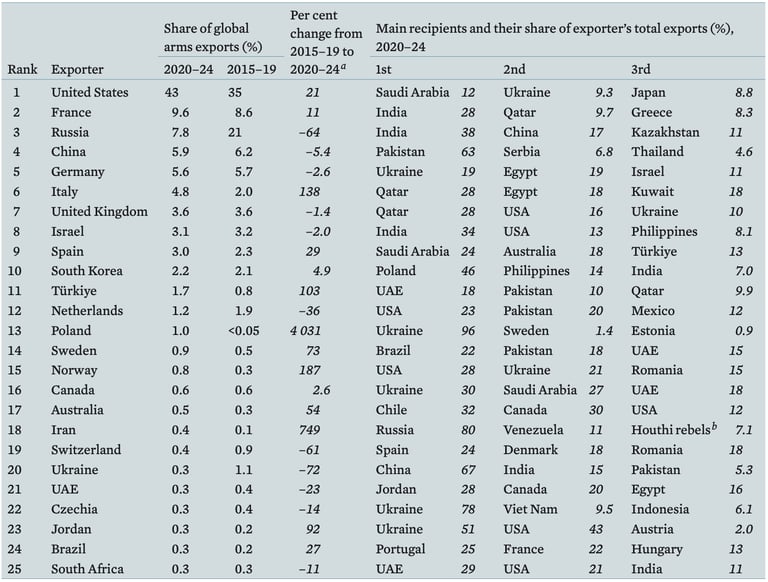

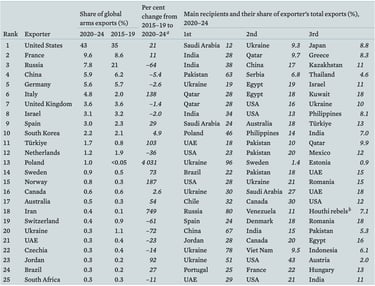

Europe is therefore not without resources. By the end of 2024, the value of all orders placed by KNDS, the company created by the merger of Krauss-Maffei Wegmann (German arms industry company) and Nexter Systems (French government-owned weapons manufacturer) in 2015, and specialized in the design and manufacture of land systems for the armed forces (battle tanks, armored vehicles, artillery systems), amounted to 23.5 billion euros, 15% more than in 2023. France has also become the world's second-largest arms exporter over the period 2020-2024 (9.6% of global arms exports), whereas it was behind Russia between 2015 and 2019 (8.6% of global arms exports versus 21% for Russia). But the big winner remains the U.S.: 43% of global arms exports between 2020 and 2024, compared with 35% of global arms exports between 2015 and 2019. Ukraine has become the world's leading importer of major weapons between 2020 and 2024, with 8.8% of global arms imports versus 0.1% over the 2015-2019 period, sourcing mainly from the USA (45% of Ukraine total imports). The same applies to European arms imports, which increased overall after 2020. European NATO members largely increased their arms imports between 2015-2019 and 2020-2024 (0.1% to 0.7%). Most of these countries source from France, Spain and the UK, but mainly from the U.S.

As a matter of fact, most European heavy investments go directly into U.S. weapon systems. For instance, several countries have signed agreements with Lockheed Martin to acquire F-35A conventional take-off and landing (CTOL) jets. Poland has signed a deal with the US government for 32 F-35A fighter jets in 2020. Denmark has also ordered 27 F-35A Lightning IIs, with first deliveries scheduled for 2023. Last January, three new F-35A Lightning II multi-role fighters were delivered to the Danish Skrydstrup base. Finally, Germany ordered 35 F-35A aircraft under its agreement with the US government in December 2024, with the first deliveries scheduled for 2026. Moreover, Polish President Andrzej Duda recently asked the USA to deploy nuclear facilities on Polish soil, in an interview for the Financial Times.

Why do NATO countries buy their weapons mainly from the U.S.? European governments order small quantities of military equipment and place their orders separately. National industries are therefore the main producers of national armies, which request systems according to criteria specific to their national needs. As a result, the European defense industrial market is fragmented, produces little and costs too much. Therefore, European countries are buying weapons from the U.S. and not Europe because: (a) it could lead to the slower arrival of certain critical weapons systems, (b) it could lead to the purchase of weapons systems with lower performance than those available on the world market (and particularly from the U.S.), (c) it could lead to higher prices for weapons systems that could be produced more cheaply elsewhere, and (d) it could provoke a reaction from the U.S., which has been supplying Europe for decades, but also receives weapons from European countries (UK and France mostly).

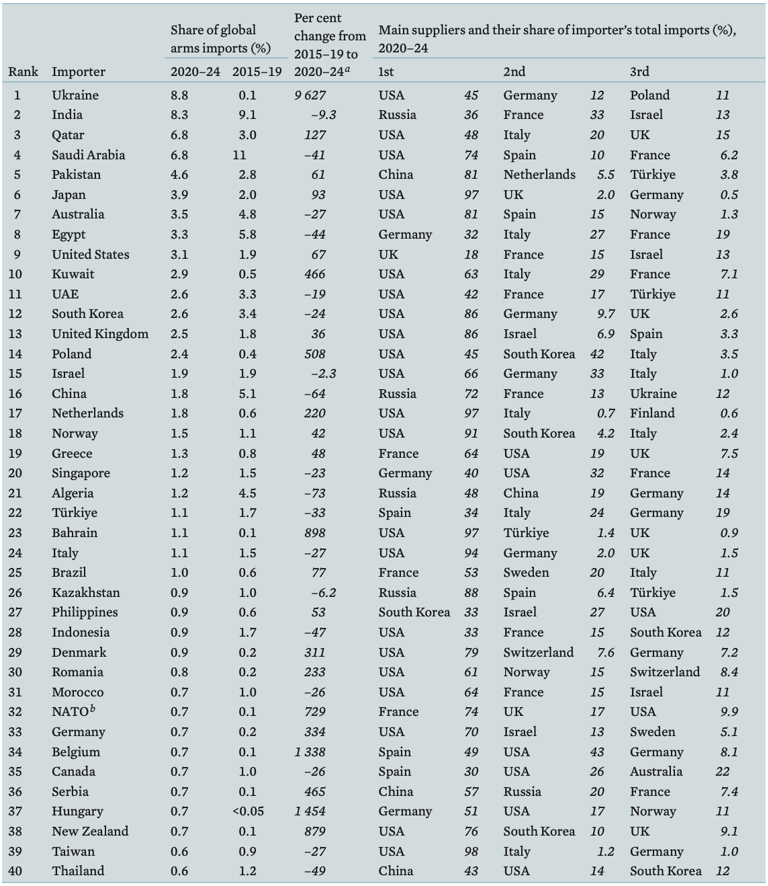

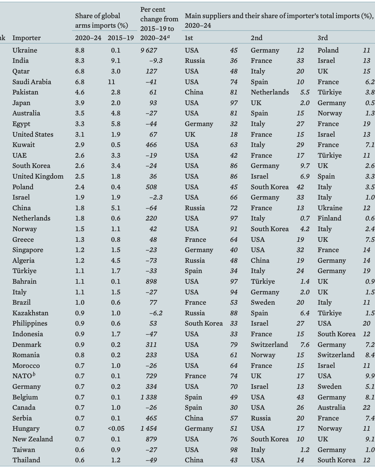

Table 4: The 25 largest exporters of major arms and their main recipients, 2020–24

Source: SIPRI Arms Transfers Database

Percentages below 10 are rounded to 1 decimal place; percentages over 10 are rounded to whole numbers.

Table 5: The 40 largest importers of major arms and their main suppliers, 2020–24

Source: SIPRI Arms Transfers Database

Percentages below 10 are rounded to 1 decimal place; percentages over 10 are rounded to whole numbers.

Finally, even as concerns continue to grow about the potential withdrawal of the US from NATO, member countries recently committed to increasing their spending on the alliance. NATO is funded by direct expenditure (0.3% of total Allied defence expenditure), which is based on common and joint funding, but also by indirect expenditure, namely contributions from the Allies drawn from their overall defence capacity. While direct expenditure finances NATO's civilian budget (secretariat, administration), the military budget (integrated command, staff, training, infrastructure) and joint investment programmes (such as the development of communication systems, surveillance or military infrastructure), indirect expenditure finances the national defence budget (purchases of equipment, salaries, infrastructure), troop deployments in NATO-led operations and material contributions (troops, aircraft, ships, equipment). The direct contribution of the Allies, or share, is calculated according to the gross national income (GNI) of the States and set for two years. In 2024, the US contribution was 15.88%, while the main contributors from the EU were Germany (15.88%), France (10.19%), Italy (8.53%) and Spain (5.82%). The other Member States all had a share of less than 2%, and in most cases less than 1%. Regarding indirect expenditure, at the 2025 NATO summit in The Hague, at the insistence of the US President, the Allies have committed to investing 5% of their Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in defence and defence spending by 2035. While 3.5% of their GDP will be allocated each year to the basic defence needs of the allied armed forces and to achieving NATO's capability goals (almost double the 2% annual target they had set themselves since 2006), the remaining 1.5% of GDP will be devoted to the defence of critical infrastructure and networks, as well as civil preparedness and innovation. Ultimately, this is a major victory for Donald Trump, who has long been pushing the Allies to increase their defence spending on NATO and purchase more American military equipment.

When it comes to supporting Ukraine, EU countries remained broadly aligned behind President Zelensky’s appeal for a just and lasting peace. His speech before the European Parliament in November 2024 was both a plea and a reaffirmation of shared values between Ukraine and the EU. “We must end this war fairly and justly”, he told MEPs, urging continued military, political, and moral support in defence of sovereignty and democracy. But despite this rhetorical unity, Europe’s consensus is beginning to fray. One such example is Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán, who has repeatedly blocked EU aid to Ukraine and resisted further engagement, openly challenging the bloc’s coherence and patience. Public opinion is also shifting. A survey by the Nézőpont Institute shows growing scepticism. Between April and May 2025, opposition to Ukraine’s EU accession increased from 62% to 67%, while support declined from 29% to 23%.

Meanwhile, far-right parties across Europe have capitalised on public fatigue and economic anxieties to advocate closer ties with Moscow, citing energy dependence and the high costs of militarisation. In Germany, for instance, Chancellor Friedrich Merz’s efforts to strengthen the Bundeswehr have drawn fierce criticism from the far-right AfD, which condemned rising federal debt and accused the government of neglecting domestic concerns and focusing on external threats.

Europe thus finds itself at a strategic inflection point. Confronted with Russia’s aggression, waning U.S. commitment, and a public opinion increasingly supportive of greater defence capabilities, the EU has been forced to rethink the foundations of its collective security. The ReArm Europe reflects this shift, but it also exposes the fault lines running through the Union: from economic disparities and industrial fragmentation to political dissent and democratic scepticism. Despite these tensions, a new dynamic is emerging. The assertiveness of the Eastern flank, renewed Franco-German leadership, and continued support for Ukraine signal that European rearmament is no longer theoretical, but becoming a political and strategic reality, albeit one shaped by internal contradictions and contested visions of Europe’s future role in global security.

Trajectories: Between Autonomy, Alliance, and Identity

Despite growing ambitions for a more autonomous European defence, the reality remains that NATO continues to serve as the cornerstone of European security, underpinned by overwhelming U.S. military power, which includes over 1.3 million troops and a vast nuclear arsenal. However, Europe is not defenceless. Major EU Member States, such as Poland, France, Germany, and Italy, each field over 150.000 troops, while France maintains an independent nuclear deterrent and a permanent seat on the UN Security Council. Since 2003, the EU has carried out 37 military and crisis-management missions within the framework of CSDP, but with a modest number of troops (around 5,000), a modest figure compared to NATO's capabilities (several tens of thousands of troops for major NATO operations).

Since 2022, EU member states have increased their military budgets and revived the idea of a common European defense. Despite these advances, European defense remains fragmented and incomplete, and NATO remains the main guarantor of the continent's security. The result is a fragmented, still-incomplete defence landscape, with persistent reliance on American support but also evident shortfalls in critical areas such as missile defence, satellite infrastructure, and above all, defence industrial integration. What’s more, as pointed out by expert Nicole Gnesotto, the primary obstacle is not material but political, where a lack of shared political will and strategic vision among EU Member States continues to stall deeper integration.

This recognition of strategic dependency, combined with the geopolitical urgency posed by Russia and the uncertainty surrounding the U.S., has catalysed a shift. European rearmament, once rhetorical or piecemeal, is now a strategic necessity. With the ReArm Europe plan, the EU commits for the first time to building a comprehensive and autonomous defence capacity, not to replace NATO, but to ensure Europe can act independently if needed. Despite being initially contested because of disagreements, von der Leyen’s White Paper on European Defence was ultimately adopted and its implementation commits the Union to a trajectory that combines military reinforcement with industrial resilience, seeking to reduce Europe’s vulnerability while affirming its role on the global stage through its normative power.

The EU now faces a delicate balancing act. On the one hand, it must redefine its collective defence posture and revise long-standing assumptions embedded in transatlantic relations. On the other, it must ensure that this strategic shift does not erode its core values. The ReArm Europe plan must thus reconcile operational autonomy with democratic oversight, responsiveness with transparency, and military preparedness with the general interest. Due to concerns about the risk of militarising Europe, at the expense of its traditional identity as a normative power, grounded in diplomacy, peace-building, and multilateralism, it will be essential to address legitimacy concerns, such as the ones put forward by the Left and parts of the nationalist Right. In fact, if poorly managed, rearmament could provoke democratic backlash, or fuel Euroscepticism in already divided societies. At the same time, the EU must be able to navigate through this to build credible deterrence in order to defend its values and interests against external threats. On top of having to deal with an aggressive Russia and an increasingly unreliable American ally, the objective for the Union is also to become a strategic actor, capable of shaping global governance, not merely reacting to it. This means diversifying alliances, strengthening partnerships beyond the transatlantic lens, and maintaining a strong presence in global diplomacy.

Clearly, the EU is at a crossroads. Rearmament is underway, but the direction, coherence, and inclusiveness of that process remain open questions. If the EU succeeds in harmonising its strategic objectives with democratic legitimacy and social priorities, it can emerge as a powerful and autonomous player on the global stage. But without a shared long-term vision, Europe risks further fragmentation, both militarily and politically. In today’s complex geopolitical realities, the challenge for the coming years is to convert current momentum into collective strategy, one that upholds Europe’s values while strengthening its ability to act. Only then, can the EU consolidate its role as both a security provider and a normative power, combining sovereignty with solidarity and ambition with accountability.

Greenlash

The EU's Climate Agenda Redefined

The formation of the new European Commission following the 2024 EP elections has marked a rightward shift in the European Union's institutional landscape. For the first time in recent history both the Parliament and the Commission moved towards a more conservative orientation compared to previous electoral cycles. Indeed, as mentioned in the introduction of this article, the traditional pro-European integration forces lost ground to right-wing and far-right parties.

Central to these changing dynamics is the political triumph of the centre-right EPP that was able to consolidate its leadership in the EP with 15 additional seats, mainly from Germany but also from Southern and Eastern Europe countries, like Poland, Greece, Bulgaria, and Croatia. At the same time, right-wing political forces as France's Rassemblement National of Marine Le Pen and Germany's Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) exploited public fatigue with green regulation as well as rural frustration with so-called elite-driven and urban climate policy. The same two Member States are the very ones where the Greens lost the most, 20 seats down from 2019.

The EPP, led by Commission President Ursula von der Leyen, increasingly echoed the rhetoric of the far right in an effort to broaden its electoral appeal. This convergence is particularly visible in Member States like France, where Marine Le Pen’s RN proposed ending subsidies for renewable energies sources, particularly wind turbines, while still nominally supporting the broader energy transition Le Pen’s stance does not reject climate goals outright but calls for a drastic slowdown in their implementation, arguing the transition “must be much slower than what is being imposed on the French”. This illustrates a broader trend of climate policy being reframed around national interests and voter feelings, even within the heart of the EU’s institutional mainstream.

Several parliamentary developments underpin this redefinition. In December 2024, the EPP supported efforts to water down the 2035 internal combustion-engine car ban, with appeals for delay, hybrid exemptions, and speeding up the review of CO2 compliance targets. Luckily, in January 2025 the Group rejected an attempt by Jordan Bardella - President of Rassemblement National and leader of PfE - to suspend the Green Deal temporarily. But in April 2025, the EP voted to delay the implementation of the CSRD (Corporate Sustainability Reporting) and CSDDD (Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence) directives, with the EPP, Renew, and right-wing factions voting in favor, de facto shielding industry from stricter environmental control . These votes reveal how EPP's transformation has materialized in policymaking, i.e., radical in rhetoric at times, more pragmatic in reality. In synthesis, it seems the EPP started to fight to reform the green regulatory ambitions based on industrial and competitiveness considerations.

On the other hand, RN MEPs repeatedly rejected major Green Deal dossiers. For example, In February 2024 they rejected the Nature Restoration Law, seen as threatening farmers and national sovereignty. Then, in November 2024, they joined a cross-party group which voted to postpone and weaken the EU Deforestation Regulation, backing amendments such as "no-risk" country exceptions. These legislative actions clearly underline RN's institutional opposition to EU climate and environmental policy.

In a September 2024 EP debate on the future of EU agriculture, right-wing and far-right groups, notably ECR, but also PfE and ESN, denounced the negative impact of climate policies on agricultural productivity and food sovereignty. Considering environmental standards as too restrictive, they called for these rules to be limited in order to preserve the farmers' competitiveness. Conversely, the Greens, the Radical Left and the S&D group insisted on the need for a profound ecological transition, but stressed the importance of putting in place social safeguards so as not to penalise small farmers. The Renew group, along with the EPP and S&D, took a more nuanced position: while recognising the climate emergency, they stated that they refused to allow the transition to rest solely on the shoulders of farmers. Instead, they called for broader dialogue, balanced compromises between farmers and environmentalists, and adequate funding to support this transformation.

This division in the EP weakens the implementation of the Green Deal in the agricultural sector, particularly because some groups, especially on the right spectrum, consider the plan to be an ideological project disconnected from rural realities. Livestock farming is a particular source of tension: conservatives denounce its stigmatisation, while environmentalists and the radical left campaign for a reduction in its environmental impact and its role in European agriculture.

These developments have drawn the attention of journalists and researchers alike, with many pointing to a broader ideological realignment that could de-green the EU’s policy agenda. Analysts and observers predict that the EU will work around a far-right majority made up of pro-Trump conservatives and former fringe actors, rather than mainstream political forces such as the socialists, liberals and greens.

The rhetorical shift is noteworthy. No longer seen as a moral duty, the green wave is increasingly being framed in terms of "pragmatism", "realism" and economic security. The buzzwords, frequently invoked by conservative and right-wing MEPs, serve as ideological justifications for policy U-turns on environmental commitments. In January 2025, Jordan Bardella justified his call to suspend the Green Deal by speaking of a “pragmatic and realistic environmental ambition in the face of the challenges we face”. In an interview published in May 2025, EPP MEP Christian Ehler, one of the architects of the Clean Industrial Deal (see below), framed the watering down of green ambitions as an acknowledgment of political and economic realities. According to Ehler, the EU had failed to lay the necessary groundwork for major economic disruption, and should have ensured a stronger industrial and social foundation before legislating such transformative climate measures. Sometimes, far-right MEPs push their rhetoric to the limit. With statements such as “the European Green Deal should be thrown in the bin” (from ESN) and “the Green Deal policies have pushed the European agricultural sector to the brink” (from PfE), these parties are calling for the "end to this harmful Green Deal" (from PfE).

These statements exemplify how “realism” and “pragmatism” are now embedded in the institutional language of both the radical right and the centre-right. What was once a movement rooted in climate justice and intergenerational equity now gives way to narratives of industrial rebirth, rural protectionism, and national sovereignty, particularly in the face of global economic competitors such as China and the United States, both of which are investing greatly in green technology while subsidizing local producers.

This dynamic has had voice in recent European Parliament debates, where disappointments with climate policy and multilateralism have speeded up. While the majority of MEPs reiterated the concept of the EU as a global player on the basis of international cooperation, democratic values, and collective responsibility for the environment, some MEPs explicitly indicated solidarity with Trump nationalism, taking openly anti-climate governance, gender rights, and immigration policy stances. Their rhetoric, framing EU social and environmental agendas as incompatible with national competitiveness and sovereignty, has gone mainstream, driving broader calls for deregulation and cultural conservatism. With slogans such as "Trump is the rebirth of democracy" and "Let's make Europe great again," parliamentary politics is symptomatic of a deepening rift between pro-EU traditionalist parties and an illiberal right in the making, a dynamic which will increasingly set the course for EU climate and democracy policy in the next few years.

Last January, President Trump decided to end the United States' membership in the World Health Organization (WHO) and to withdraw the country from the Paris Climate Agreement. In response to this decision, far-right groups (ESN, NI) expressed their radical rejection of climate commitments, celebrating Trump’s decisions. They describe the climate crisis as a “psychosis” or a “fraud,” defend national sovereignty against what they call “globalitarianism”, and oppose what they perceive as a “punitive doctrine” imposed on European citizens. This nationalist economic discourse rejects the collective and international dimension of the fight against climate change. The EPP has taken an intermediate position: while criticizing the Trump administration for its climate cynicism, it defends a strategic partnership between the EU and the US and promotes a “technology-neutral” approach, emphasizing the exemplary role that Europe must play.

However, Trump’s decision also gave rise to pro-European discourses, from the center to the radical left, emphasizing the need for the EU to assert itself as a leader in the global fight against climate change. The majority of European political groups agreed on the seriousness of global warming and the need for strong, coordinated, and ambitious action. During a debate in the EP, the European Commission stressed that the EU remains the main international climate donor, with $30 billion committed in 2023 to support the energy transition in line with the goal of limiting warming to 1.5°C. While groups like S&D insisted on international cooperation as the only viable path in the face of right-wing climate nationalism, the Greens emphasized that the EU must remain a global role model, despite the US withdrawal, by adopting binding targets for 2030 and 2040 .

Prior to the rise of radical right parties such as the ECR and the eventual formation of the PfE and ESN groups following the June 2024 elections, political tides had already begun to shift. Key tenets of the European Green Deal were slowly diluted, not only at the initiative of radical forces, but also through strategic repositioning by mainstream parties. A relevant example was the EPP's resistance to the Nature Restoration Law, one of the Green Deal's flagship components. Though the law was finally approved, it did so by a small margin and only after an internal split in the EPP, indicating how fragile the political climate consensus had become, even among traditionally pro-European forces. Other provisions tied to agriculture, like crop rotation, were rolled back during farmer protests, further showing how environmental ambition was increasingly subordinated to electoral concerns and economic anxieties.

More broadly, the Green Deal has progressively become a matter of contention for a fractured but widening coalition of green-sceptics, where parts of the centre-right, including certain members of the EPP, ally with more radical forces. While often divided on other matters, they have strategically aligned to water down or delay key elements of EU environmental policy, symbolising the formation of a more polarized and contentious legislative environment for climate action. This convergence does not always translate into official blocs, but has formed a new "blocking majority" with the capacity to redefine the ambition and scope of the EU's climate agenda.

The New Logic: Deregulation and Industrial Pragmatism

Political Shifts in Institutional Framing

The political context that enabled the ambitious climate action of the first Von der Leyen Commission, marked by mass grassroots mobilisation, strong Green representation, and transatlantic momentum, has fundamentally changed. The current term opens with a fragmented Council, more right-leaning than before, and a global environment marked by strategic insecurity: war in Ukraine, instability in the Middle East, and the return of Trump to the EU presidency. These overlapping factors have elevated not only industrial but also defence policy as EU priorities, reducing political bandwidth for climate leadership. At the same time, the Draghi report’s warning of stagnating competitiveness has reinforced the narrative that green regulation must not come at the expense of economic strength. By no longer positioning itself as a normative climate leader, the EU seems to be balancing climate ambition against geopolitical, fiscal, and industrial constraints.

In the context of the election results, the decline of the Greens and the Liberals is significant, as they had previously driven the European Green Deal forward alongside the Socialists. The EPP, strengthened from the election results, has been claiming leadership over the new direction of climate policy, whose priority is being moved from ambitious environmental reform to industrial competitiveness. This shift redefines the EU’s climate strategy as an economic growth engine and introduces a more pragmatic approach that may dilute previous environmental commitments in favour of deregulation and market-oriented goals.

The institutional reorganisation of the new Commission offers further evidence of a policy shift in climate policies. Putting away the executive vice-president for the European Green Deal and replacing it with a vice presidency for a "clean, just and competitive transition" was a strategic move. Specifically, climate ambition seems to be placed together with, if not replaced by, competitiveness and innovation rather than being a transformative agenda in itself. Similarly, the title for the current Commissioner for Climate, Net Zero and Clean Growth is a discursive move in the direction of industry-sensitive language, emphasizing growth and decarbonisation to the detriment of broader ecological objectives. While not an abandonment of climate policy per se, it suggests a redirection: fewer radical changes, more gradual, market-appropriate reforms.

Even before the formal announcement of the Clean Industrial Deal, several researchers had already foreseen that the next “update” of the European Green Deal would be a tipping point, less regarding environmental ambition, but rather about industrial competitiveness. Initially referred to by some as the "Green Industrial Deal," the strategy under development was framed as a complementing pillar to the existing Green Deal. But policy watchers warned it could represent a major shift away from binding climate policy towards shielding European industry from global competition. Rather than securing the EU's position at the forefront of the world's green transition, the strategy appeared more driven by concerns over economic stagnation and geopolitical instability. The risk, as noted by observers at the time, was that such a change would dilute or delay existing green commitments in the name of economic pragmatism.

As anticipated, this change in tone signals a broader ideological reorientation of the Union’s agenda, from the climate-centric ambitions that defined the von der Leyen Commission’s Green Deal towards a new policy framework centred on sovereignty, competitiveness, and energy security. The EU seems de facto to be reframing its priorities: climate change is no longer treated as the existential policy challenge of the decade, but rather as one issue among many, often subordinated to economic or geopolitical concerns. The ongoing debates over the upcoming revision of the Fit-for-55 legislation, originally designed to reduce the EU greenhouse gas emissions by 55% by 2030, then lowered to 40%, and the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) reflect this recalibrated approach, where environmental standards risk being watered down to accommodate sceptical national governments and economically vulnerable constituencies.

This strategic reorientation culminated in the unveiling of the Clean Industrial Deal, a flagship initiative signalling the EU’s evolving climate-industrial nexus. Introduced within the first hundred days of the new Commission, this project has been framed as a continuation of the Green Deal (or Green Deal 2.0), but actually rebrands the EU’s climate agenda around market logic, aiming to support industry competitiveness rather than impose stringent green obligations. Centering clean energy as a driver of economic growth, the Clean Industrial Deal will focus on three key goals: accelerating decarbonisation, enhancing competitiveness (especially after the energy crisis), and boosting resilience through strategic de-risking. The plan targets the clean tech sector and energy-intensive industries, and is built on six pillars: affordable clean energy, demand for green products, increased transition financing, circular economy mechanisms, international green trade partnerships, and focus on workforce resilience.

The votes leading to the approval of the Clean Industrial Deal, including the consent by EPP, S&D, Renew and the Greens, and the rejection by ESN, PfE and the Left, highlight once again a political realignment in the EP around the climate issue. The pro-European axis seems to be working on a renewed vision of climate policy, more focused on industrial competitiveness and energy security. On the other hand, the opposition considered the compromise to be insufficient: too liberal for the left, too European and regulatory for the far right. This vote marks then a change of direction in European climate policy: from normative leadership to a strategy of green industrial power, bringing together moderates, liberals, and some environmentalists, at the cost of fractures with more ideological forces.

Legislative Rollbacks

At the same time, some legislative reversals have occurred. In the automotive sector, CO2 reduction targets were diluted and postponed. Originally part of the Fit for 55 package, the emissions standards required new cars and vans to reduce average CO2 emissions by 15% by 2025 and by 100% by 2035, effectively ending the sale of new petrol and diesel vehicles in the EU. The revision recently adopted introduces greater flexibility: instead of meeting targets every year, manufacturers can now average their fleet’s CO2 performance across the 2025–2027 period. This allows them to offset excess emissions in one year by outperforming the target in another.

This time, most EP groups voted in favour, except the Greens and the Left, confirming again a readjustment of the EU's climate ambitions in favor of a more flexible approach, dictated by industrial tensions in the automotive sector, especially in the face of Chinese competition. The automotive industry lobbies, including ACEA, have then welcomed the EU decision as necessary flexibility in the face of sluggish sales of electric vehicles and overall economic pressure. But they have also called on the EU to implement more robust public incentives and faster deployment of charging points to support the transition to zero-emission vehicles. Critics highlight that these alternatives will result in fewer electrical vehicles and total increased emissions, and eventually slow down the speed towards climate goals and undermine the EU's long-term green ambitions.

In the meantime, broad deregulation has begun, including exempting 80% of companies from sustainability reporting requirements. These setbacks regard the CSRD and the CSDDD, requiring firms to publicly disclose environmental, social and human rights risks in their operations and supply chains. In this case, the substantial EP approval show that the political divide is no longer between pro-climate and anti-climate, but between those who want to regulate quickly and strongly, and those who advocate for a gradual approach, aiming to reconcile sustainability and competitiveness.

The EU's new 2040 climate target, once proposed as a legally binding 90 percent reduction of greenhouse gas emissions from 1990 levels, has come under pressure. Limited support for a loophole-free target came from a POLITICO survey of 27 national ministries. Most member states urged alternatives such as carbon credits (purchasing emission allowances instead of reducing one’s own emissions), negative emissions (removing CO₂ from the atmosphere), and phased-in compliance (gradually applying the rules), reflecting a preference for flexibility rather than strictness.

The Commission initially postponed a formal proposal until the summer's eve and signaled openness to providing concessions such as carbon capture and storage (CCS), a technology that captures CO₂ from industrial processes and stores it underground to prevent its release into the atmosphere, and altered routes. These can be seen as overtures to deal with growing domestic lobbying and industrial pressure, particularly in Germany and Italy, where national governments and the EPP have lobbied for weaker enforcement mechanisms. The Commission eventually proposes allowing up to 3% of the target to be met using international carbon credits from verified projects abroad, starting in 2036. This deviation from inflexible goals demonstrates how economic feasibility is increasingly prioritized over transformative climate ambition.

Following the elections of 2024, the EU accelerated its deregulatory path by keeping green policymaking away from technical experts. Member states increasingly used the practice of passing on duties to diplomats and political negotiators for quick red-tape reduction rather than science-driven policies. This strategy often leads to political compromises rather than evidence-based solutions developed by environmental experts. This was seen in the adoption of broad "omnibus" simplification packages targeting several sustainability commitments in areas like chemicals, agriculture, and energy. In particular, the European Commission proposed excluding 80 percent of companies from requirements to report on sustainability. In the meantime, critics warned that dismantling the expertise erodes policy quality and makes EU environmental regulation more vulnerable to industry lobbying. This shift from expertise-based regulation towards politically driven deregulation is evidence of a structural change in how regulatory green policy is being constructed and implemented.

Another not-so-reassuring development has been the effective ditching of the EU's anti-greenwashing directive, which was initially designed to prevent firms from making false environmental claims. The proposal, which would have banned product labels like "climate neutral" or "eco-friendly" unless scientifically supported, was first put on hold by the Commission, prior to falling apart completely after Italy pulled out of negotiations, with other member states joining it . Without this directive, consumers may be misled by vague or unverifiable eco-claims on products, undermining informed environmental choices. These acts not only illustrate retail and industry group lobbying pressure, but also a broader deregulatory context within which even low-cost, high-impact measures meet political resistance. Furthermore, transparency and consumer rights, historically at the center of EU environmental and market integrity, are increasingly being sacrificed in the name of flexibility and competitiveness.

In this context, European policymakers increasingly speak of a “level playing field”, making sure that EU companies face similar rules and costs as global competitors, using industrial policy as a way to regain strategic leverage, even if that means relaxing or delaying green ambitions. The Net-Zero Industry Act (NZIA), presented as a pillar of Europe’s new green industrial approach, reflects this framing: it priorities scaling up domestic production of clean technologies over stringent environmental targets. As a result, the rightward turn of the European institutions represents not merely an electoral trend but a structural recalibration of the Union’s priorities.

The European Commission is recalibrating its approach from regulatory ambition to pragmatic implementation, often in response to political and social pressures. Ursula von der Leyen appears to be proceeding with a cautious "amputation" of the Green Deal, removing the most controversial elements in an effort to preserve its core essence, and specifically preserving the 2050 net-zero target. The idea is to strike a delicate balance, trimming regulatory action only sufficient to appease EPP and far-right MEPs, but maintaining what remains of Europe’s long-term climate vision. This approach reflects a choice from transformation to survival: abandoning short-term green aspirations in the interests of maintaining political cohesion and fighting for core climate objectives. EPP President Manfred Weber has also recently stressed the need for defensive pragmatism. He stated that he prioritizes the protection of Europe's industrial base and the EPP’s distancing from far-right forces, even as he keeps collaborating with them in rebalancing climate policy accordingly.

Hitting the Ground: Rural Backlash, Populist Fuel, and Public Confidence Erosion

The farmers' protests which swept across much of Europe earlier in 2023-2024, from Poland to France and to the Netherlands, were probably the symbolic epicentre of this backlash. Although cast as a revolt against rising fuel prices and excessive bureaucracy, they were also actively funded and repeatedly instrumentalized by far-right parties, aimed against the dismantling of environmental protection. The protests thus came to symbolize a more general "greenlash", i.e. convergence of rural discontent, economic anxiety, and growing cultural resistance to progressive climate policies. Here, the political centre began to fragment, and mainstream parties like the EPP began appropriating right-wing narratives in an attempt to retain voter support, especially in more traditional rural constituencies.

The EPP’s realignment is more and more evident: the group recently joined a cross-party effort, led by the ECR and PFE groups, to audit and possibly defund environmental NGOs, despite the tiny EU funding involved. The step would cut out almost 70% of the annual total income for about 30 NGOs (around €15.6 million, or 0.006% of the EU budget). The move shows a change from seeding regulatory barriers towards delegitimization of civil society organizations critical of the green transition.

Long before the 2023-24 farmers' uprising, a precedent for a working and rural class backlash to green legislation had been established with the 2018-2019 Yellow Vest (Gilets Jaunes) movement in France, and its Italian counterpart, the Gilet Gialli. Originally set off by opposition to a proposed fuel tax, the protests quickly broadened into a broader rebellion against perceived elitism in environmental and fiscal policy-making. The RN supported the protesters, placing green taxation as a threat to rural and working-class livelihoods. This example explains that greenlash is not new nor solely agriculture-related, and underlines how socially vulnerable groups are capable of teaming up against EU-backed environmental reforms, a paradigm which still fuels contemporary protests.

Another evident example concerns the free trade agreement signed by the EU and MERCOSUR at the end of 2024, since it was strongly opposed by different society sectors and other organisations. Farmer unions such as France's FNSEA (Fédération nationale des syndicats d'exploitants agricoles) and Germany's Bauernverband (the largest agricultural and forestry professional association of the country) have voiced their opposition by warning of unfair competition from imports. Environmental NGOs like Greenpeace and CAN Europe have mobilised through public letters and actions to voice the perceived undermining of European ecological standards . Increasingly, campaigners are pointing to a growing trend of environmental policy rollback and deregulation drive across the EU. What was once considered fringe is now quickly transforming into political mainstream, sparking warnings that decades of hard-won progress risk unravel unless civil society continues putting sustained pressure.

Public opinion, however, remains mostly supportive of actions against climate change. Europeans still regard the climate crisis as a serious issue and support inclusive climate policies, even though this support is conditional: farmers, small businesses, and rural communities regularly oppose policies that they view as costly or discriminatory, highlighting the importance of an equitable and socially responsible Green Deal capable of maintaining political support.

Public awareness about environmental action seems to remain high across the EU according to recent Eurobarometers. In 2023, 77% of EU citizens claimed to have considered climate change a very serious problem. 78% also agreed that environmental issues directly affect their daily life and health, and 84% affirmed that EU green policies are needed in order to protect the environment in their nation. More recent results confirm this trend. By June 2025, 85% of Europeans continue to regard climate change as a serious global threat, and 81% support the EU's goal to become climate neutral by 2050. 77% say that the cost of damage caused by climate change outweighs the cost of transitioning to a climate-neutral economy. Yet in a survey about young people's concerns, environment and climate change were put in second place, while security and defence are regarded as the EU's biggest issue, perhaps showing a generation shift in the way environmental concerns are presented within broader geopolitical anxieties.

Furthermore, in 2024 the European Investment Bank Climate Survey found that 94% of Europeans support taking action to adapt to climate change, reflecting broad consensus for proactive action despite growing political polarization. Yet this support comes alongside an expanding trust deficit: although Europeans still wish to address climate change, citizens are ever more skeptical of their governments' determination to follow through on green commitments, especially where these clash with short-term economic or electoral priorities. This dichotomy between mass aspirations and institutional delivery can potentially further alienate citizens, raise greenlash sentiment, and erode long-term democratic legitimacy for the green transition.

Interesting data arise also from the European Parliament's Winter 2025 Eurobarometer, confirming the shifting of public priorities. While support for climate action remains high, only 21% of EU citizens today place climate change and the reduction of emissions among the top priorities for the European Parliament, 6 points less than in early 2024. This must be read in the context of growing concern over inflation, security, and economic hardship, considered as top priorities by EU citizens. The data also show that young Europeans (between 15–24 years old) are more likely to rank climate action as a top priority than older generations, and individuals with fewer financial concerns are also more climate change-aware than those who struggle to pay everyday bills. Clearly, climate policy remains popular but its relevance is increasingly filtered through lenses of economic security and generational experience, a tension that may reshape the EU ecological agenda in the coming years.